Test-Driven Development "styles" Classicist (Detroit/Chicago) vs Outside-in (London)

Historical Context of TDD

Test-Driven Development (TDD) has evolved significantly since Kent Beck formally introduced it in the early 2000s with his book Test-Driven Development by Example. and even before that. What began as a foundational technique for improving code quality and design has expanded into various interpretations. Two prominent styles have emerged:

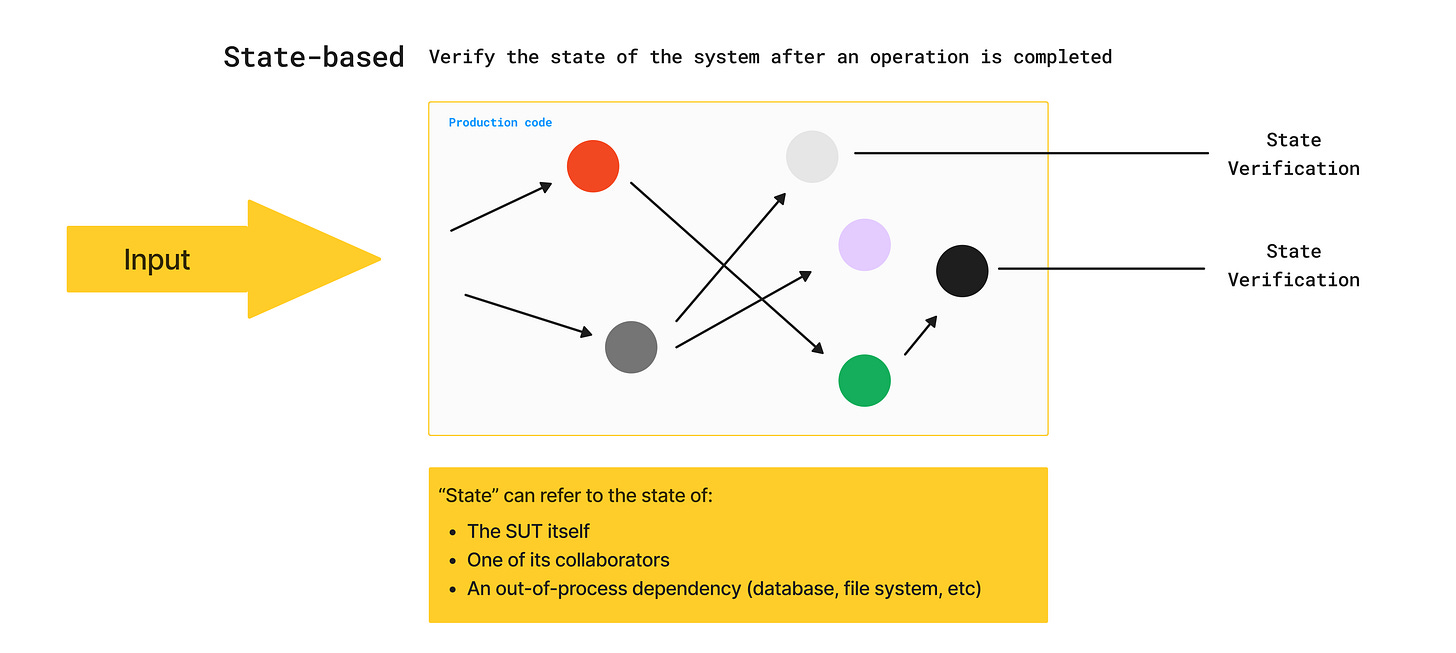

Classicist or Chicago/Detroit Style: Rooted in Kent Beck's teachings, emphasizing state-based and output-based verification and incremental design.

London Style or Mockist Approach: Popularized by Steve Freeman and Nat Pryce in their book Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests. This style emphasizes outside-in design, interface discovery and used interaction-based verification with mock objects as design feedback tools.

Although one of the most widely recognized differences between both "styles" by the community is:

Tools for isolation.

Tools to get feedback on design.

Both “styles” gained traction through educational efforts, including video courses and workshops like Uncle Bob (Chicago style) and Sandro Mancuso (London style).

These videos came out later than the books, and I would say that none of the approaches shown truly define what is written in the reference books. While it's true that they show us a way to apply both "styles," this doesn't mean they represent what the authors intended to convey in the books.

For example, the style Sandro shows is not the one that appears in the book Growing Object-Oriented Programming: Guided by test.

The first time the word “Style“ came up was in the book Growing Object-Oriented Programming: Guided by test where Kent mentioned this.

The Classicist or Detroit/Chicago “Style”:

Historical Context

The "Classicist" or "Chicago" style stems from Beck's early work, emphasizing TDD as a way to design systems incrementally. While often associated with an "inside-out" approach, this term was coined by the London School community and doesn't accurately represent Classicist TDD, which doesn't prescribe a specific starting point in system development.

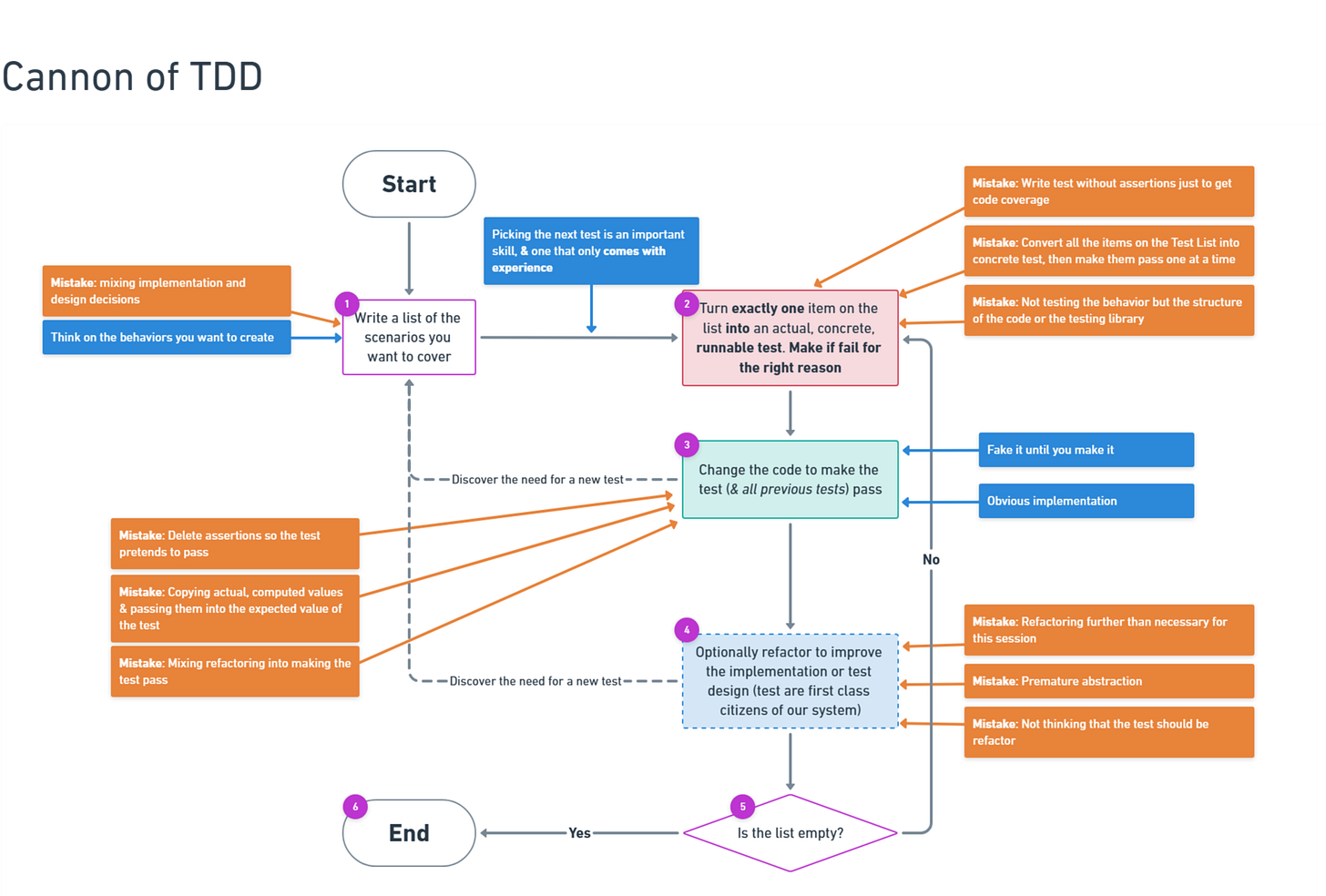

The cannon of Classicist “style”

Misconception About Classicist Style Design

Contrary to the London School’s interpretation, the Classicist Style does not strictly follow an inside-out approach. Instead:

It organically evolves design by writing tests focusing on end-to-end behavior and refining the code as needed.

It allows abstractions (interfaces) to emerge naturally, rather than forcing them upfront.

The approach values simplicity and minimalism while avoiding premature optimizations or over-engineering.

Mashooq Badar’s clarification highlights that the Classicist Style was never meant to focus solely on low-level components first, this is a mischaracterization imposed by the London School to differentiate their methodology. Instead, the Classicist Style can start from any layer, whether high-level or low-level, depending on the context.

Defining Characteristics

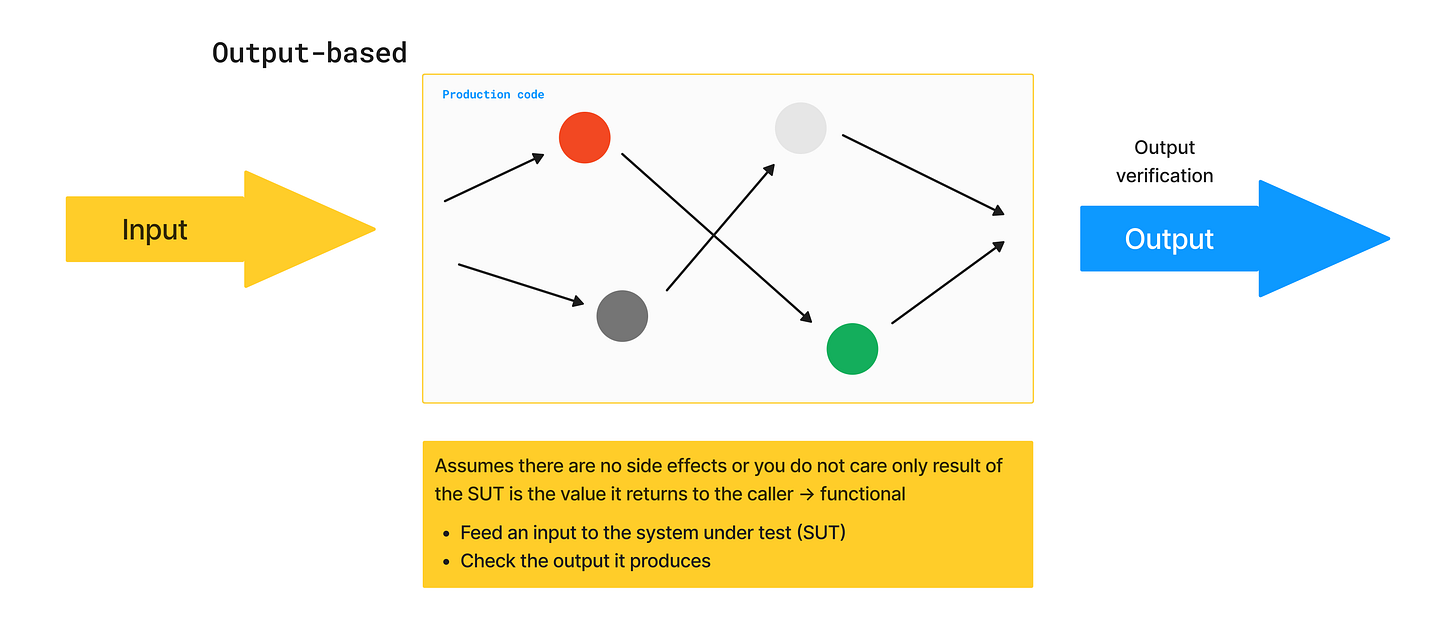

Focus on State and Output: Tests validate state changes or outputs rather than interactions between objects, unless there is a violation of the FIRST Principles, in which case they use interaction-based verifications.

Incremental Design: Design emerges organically from the process of writing tests and implementing solutions.

Real Implementations: Relies on concrete implementations rather than test doubles unless unavoidable.

Behavior-driven: Tests assert the expected behavior of the system rather than how components interact internally.

Potential Trade-Offs (when poorly implemented)

Complex Domains: May struggle to handle intricate systems with multiple dependencies or abstract boundaries.

Waste from Refactoring: Frequent small steps can lead to higher refactoring overhead, especially if not managed well, although this could also help in many other cases.

Boundary Decisions: Critics argue that starting without an upfront design could lead to inefficiencies, though this depends on the specific situation.

The London Style

Historical Context

The London style emerged from Steve Freeman and Nat Pryce's work as pioneers of test doubles. Their seminal paper on mock objects and subsequent book Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests established this approach. Sandro Mancuso later championed it, highlighting its value in complex systems.

Cannon of London “style”

Defining Characteristics

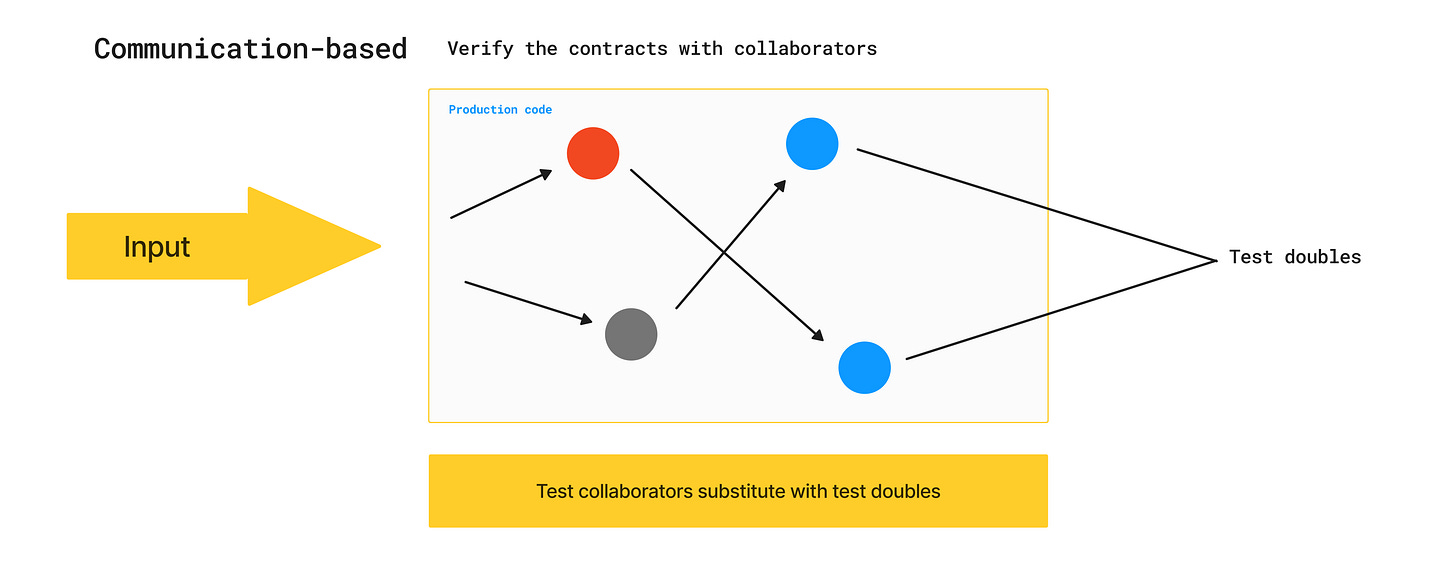

Interaction-Based Testing: Tests validate communication between objects using mocks and stubs.

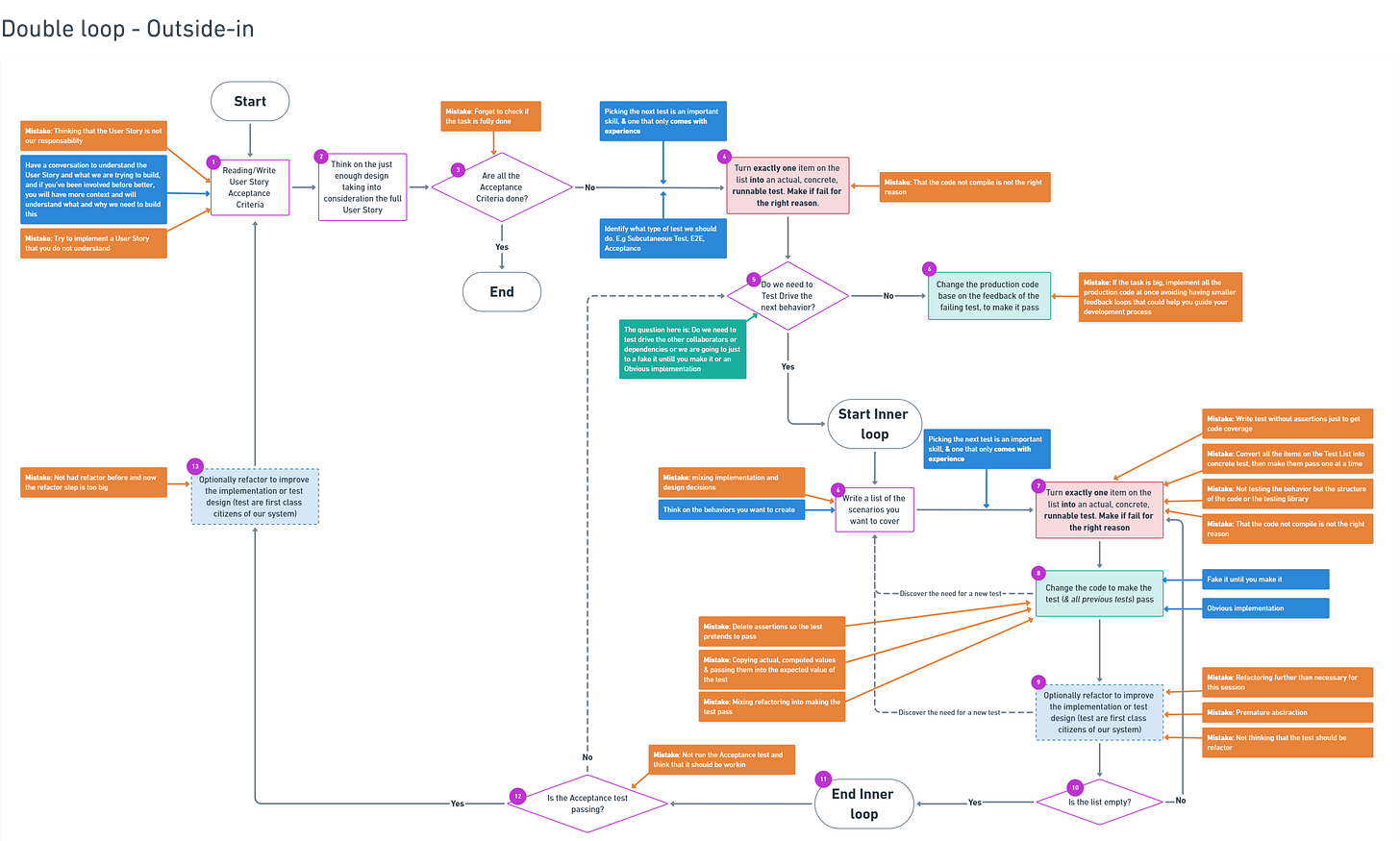

Top-Down Design: Starts with high-level behavior or acceptance criteria, moving toward the system's internals or domain.

Just Enough Design: Encourages lightweight, minimal upfront design to outline system APIs and interactions.

Behavioral Collaboration: Focuses on message passing and collaboration between system components as part of the domain.

Incremental Design: Design emerges organically from the process of writing tests and implementing solutions.

Potential Trade-Offs (when poorly implemented)

More design knowledge required: Demands a solid understanding of software design principles and architectural boundaries.

Mock Trauma: Overuse or misuse of mocks can lead to brittle tests tied to implementation details.

Overengineering: Without careful constraints, the focus on interactions may lead to excessive abstraction or unnecessary complexity, or when the practitioner does not apply YAGNI properly.

Limited Feedback on How to Build: Provides feedback on correctness but less guidance on component construction, in case of poorly implemented style.

The difference for me

A common oversimplification in discussions about the Classicist and London styles of TDD is the distinction between solitary and sociable unit tests. While this may appear as the key divergence, it's not the core difference, at least not if we return to the source materials.

In Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests (GOOS), Freeman and Pryce never claim that you must write solitary unit tests. In fact, they are clear about the boundaries: “Don’t mock values” and “Only mock peers, not internals.” This highlights that sociable unit tests are entirely valid within the London style, so long as we mock behavioral collaborators, not structural details.

A recent article by Manuel Rivero helps clarify this misconception:

👉 The class is not the unit in the London school style of TDD

Not only this, but I also wrote about the topic:

In relationship to this Martin Fowler also mention this: https://www.youtube.com/live/z9quxZsLcfo?si=Qz8FX5NiTcwLdXwH

The real difference lies in design intent.

The London style doesn’t just verify behavior, it treats tests as a design tool. You drive your architecture by expressing expectations in terms of collaborators’ roles. This leads to intentional interfaces and separation of concerns. You build systems that are easy to grow and refactor.

when you do TDD outside-in, you're not verifying behavior, you’re verifying your design is correct.

- Sandro Mancuso

To wrap up, I personally don’t think “London” and “Classicist” should be treated as fixed schools or “styles” anymore. They are tools in our toolbox. And as always in software, context matters.

Also, I believe that part of the confusion around the so-called Chicago vs. London “styles” comes not from the original authors but from how some advocates, particularly public figures and trainers, have chosen to present these ideas over time.

I want to point out that many misunderstandings come from popular educators or promoters, who often reduce concepts to easily sellable narratives. In my view, some of these simplifications might be commercially motivated, though that's just my opinion.

Let’s take some examples from Sandro Mancuso’s public talks, where he describes characteristics of Inside-out TDD (which he often associates with the classicist approach) that can be misleading or partial:

“Design happens during the refactoring phase.”

“Tests are normally state-based.”

“Mocks are rarely used unless isolating external systems.”

“No up-front design; design completely emerges from the code.”

“State is often exposed just for testing.”

“Refactoring is larger and sometimes skipped.”

“The unit becomes bigger than a class.”

“It can be slow and wasteful.”

All of these statements deserve context or counterbalance:

“Design happens during the refactoring phase” — Kent Beck also talks about obvious implementation, which is an intentional, minimal design step before refactoring.

“Tests are normally state-based” — or also, output-based. There's nothing inherently wrong with that.

“Mocks are rarely used.” — Back then, mocks as we know them weren’t widely available. Developers wrote and maintained their own fakes or stubs manually.

“No up-front design” — Kent never says that. The focus of his book is on the discipline of TDD, not on design. And let's not forget: he was a precursor of CRC cards.

“Refactoring is larger” — This entirely depends on the practitioner and their feedback cadence, not the technique.

“Unit becomes bigger than a class” — Why is that a problem? If behavior is your unit, multiple classes may emerge naturally.

“Inexperienced practitioners skip refactoring” — Yes, but that’s not a fault of the approach—it’s a matter of practice maturity.

“It can be slow” — It can, but only if misapplied. The same applies to any technique.

That said, Sandro also has some of the most balanced and thoughtful takes on the topic when he's not contrasting extremes. For example:

“Which TDD style should we use? Both. All. They are just tools and as such, they should be used according to your needs. Experienced TDD practitioners jump from one style to another without ever worrying which style they are using.”

- Sandro Mancuso

And he makes excellent points on the distinction between micro and macro design:

“Micro design is what we do while test driving code, mainly using the classicist approach.”

- Sandro Mancuso

“Macro design is normally taken into account when using Outside-In TDD, but Outside-In on its own is not enough to define the macro design of an application.”

- Sandro Mancuso

“Extremes are bad. We are going from BDUF (Big Design Up Front) to no design at all.”

- Sandro Mancuso

These quotes show that Sandro acknowledges that both Inside-out and Outside-in TDD are part of the same toolbox. The problem is when oversimplified versions of these ideas are repeated without historical or technical nuance.

Conclusions

Test-driven development (TDD) has evolved significantly since Kent Beck created it. What began as a single approach has transformed into two recognized paths: the Detroit/Chicago (Classicist) and the London (Mockist). However, these aren't separate visions or rigid styles but complementary facets of the same practice.

Rather than viewing them as distinct styles, we should see them as tools in our TDD toolkit, each suited for different scenarios based on the problem, project context, and team expertise.

Historically:

Kent Beck established the foundations known as the Detroit/Chicago or Classicist style.

Steve Freeman and Nat Pryce's Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests expanded TDD's capabilities, providing new tools for tackling different challenges.

These approaches work together synergistically:

Classicist TDD excels in its simplicity and clarity, providing an ideal foundation for learning and exploration.

London TDD shines when handling complex system design, especially where component interactions are crucial.

In my experience with Outside-in practitioners like Sandro Mancuso and others, I've noticed they often portray "Fake it until you make it" as if it were the only approach in the Classicist Style of TDD, a concept Kent Beck emphasized in "TDD by Examples." While Beck's book used simple examples to teach the technique's fundamentals rather than demonstrate complex system applications, this doesn't necessarily limit the scope of "obvious implementation" or software design in it self like Kent Beck mentions in this clip. https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxzFMEM-9hOK0LfvggyxhnAcx50jh_jtod?si=vln_xMFKrcYQr9xI

Key Takeaways

Complementary Tools: Rather than competing methodologies, the Classicist and Outside-in complement each other within TDD.

Adaptation and Context: Skilled practitioners use elements of both “styles” based on system complexity, team expertise, and domain requirements.

Evolving Practice: TDD continues to grow, blending principles from both schools of thought to meet modern software challenges.

Experienced practitioners naturally blend both approaches, choosing the right tool based on their specific needs. Understanding that these are tools rather than competing styles enables us to apply TDD more effectively and flexibly.

I have a suggestion for anyone reading this post: do not use the term "inside-out" as it does not reflect what it does; refer to it as "Classicist" instead.

References:

Beck, Kent. Test-Driven Development: By Example.

Freeman, Steve; Pryce, Nat. Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests.

Osherove, Roy. The Art of Unit Testing (Second Edition).

Khorikov, Vladimir. Unit Testing Principles, Practices, and Patterns.

Gärtner, Markus. ATDD by Example: A Practical Guide to Acceptance Test-Driven Development.

Meszaros, Gerard. xUnit Test Patterns: Refactoring Test Code.

Freeman, Steve; Pryce, Nat. Mock Roles, Not Objects. Link.

Falski, Maciej. Detroit and London Schools of Test-Driven Development. Link.

Booth, Adrian. Test-Driven Development Wars: Detroit vs London. Link.

London TDD vs Detroit TDD. NCRunch Blog. Link.

Cooper, Ian. TDD Revisited. Link.

Farley, Dave. Are You Chicago or London When It Comes to TDD? Link.

C2 Wiki. Original TDD Guidelines. Link.

Uncle Bob; Mancuso, Sandro. Curso de TDD. (Video course).

Mancuso, Sandro. Mocking as a Design Tool. https://www.codurance.com/publications/2018/10/18/mocking-as-a-design-tool

Mancuso, Sandro. A Case for Outside-In Development. https://www.codurance.com/publications/2017/10/23/outside-in-design

Mancuso, Sandro. Does TDD really lead to good design?. https://www.codurance.com/publications/2015/05/12/does-tdd-lead-to-good-design

Rivero, Manu. The class is not the unit in the London school style of TDD. https://codesai.com/posts/2025/03/mockist-tdd-unit-not-the-class

Hey Emmanuel, there's a subtle typo "Sandro Manucso". Thanks :)