A complete guide to Pair Programming

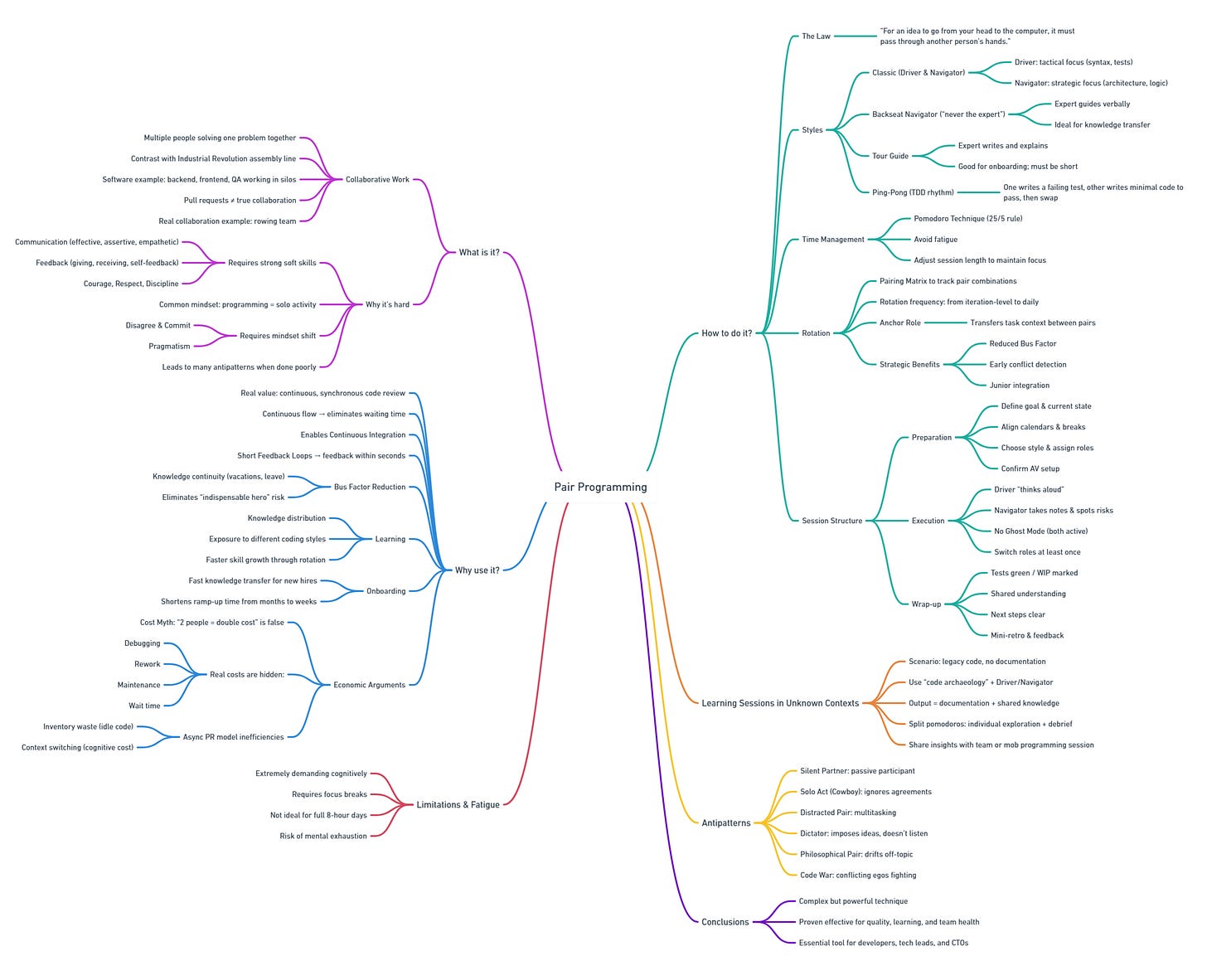

What is it?

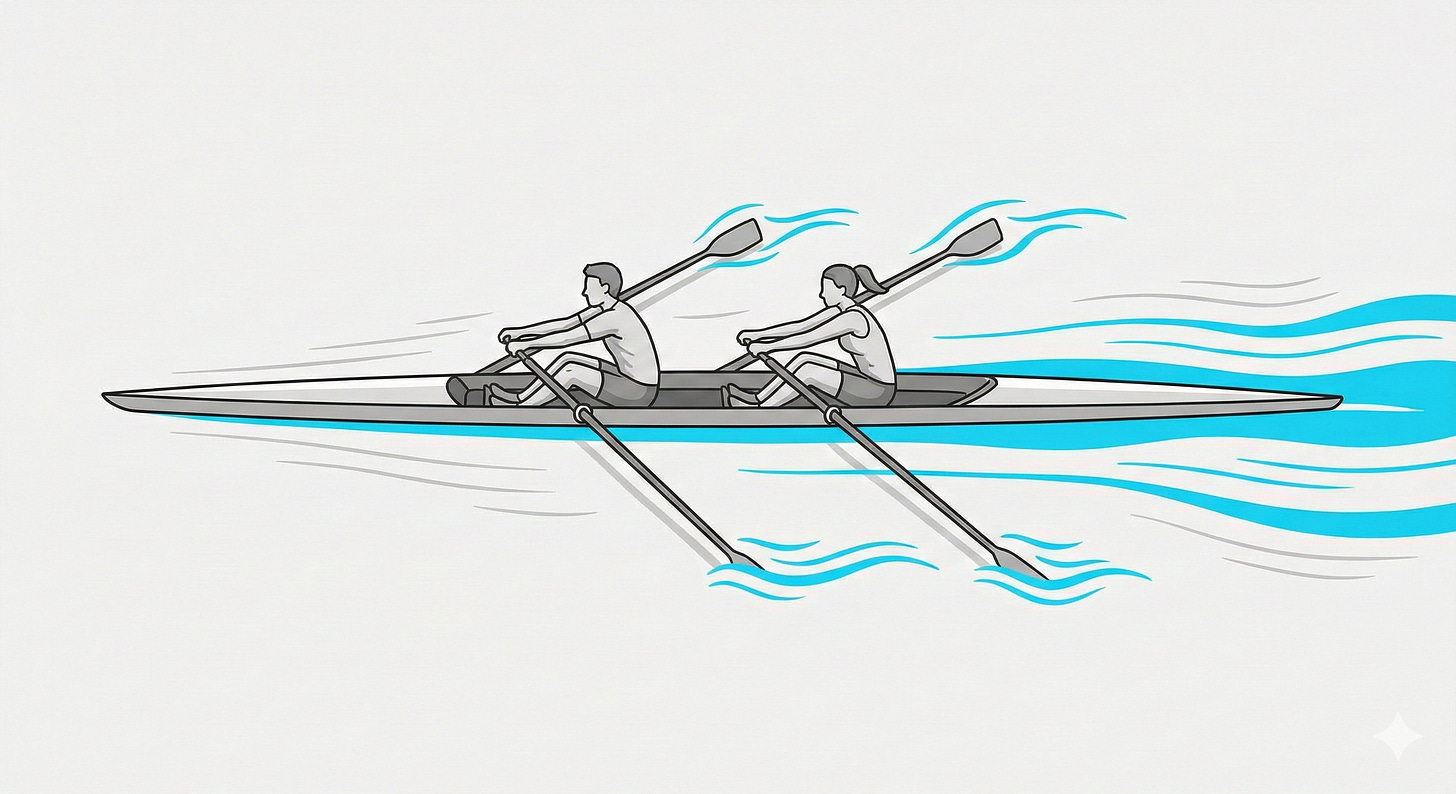

Pair programming is a collaborative working session. Collaborative working sessions are those where more than one person works together to solve the same problem, in a coordinated way.

I’ll try to explain, with an image, what the difference is between collaborative work and non-collaborative work.

A lot of today’s jobs, and in fact a big part of how we think about work today, comes from the Industrial Revolution and the factory assembly line idea: one worker does a part, then another worker does the next part, until the end of the line.

For example, in software: the backend implements what’s needed in the API, the frontend builds the interface that consumes the backend data, and QA evaluates the quality of what was built. Even if this can look “collaborative”, or we’ve been sold that it is, in reality it isn’t. Collaboration is basically limited to a predefined contract about what each step will deliver, and everyone works around that. If something changes, it has to be handed over. That’s the only “collaboration” this model has.

In software we also have pull requests, where someone evaluates the work done to check its quality. Some people say this process is for sharing knowledge, but what’s clear is that, as I said before, this doesn’t fit the idea of collaborative work, at least from my point of view. Let’s look at a real example in sports.

In this picture you can see, on one side, a factory line like the one I described above, and on the other, what for me reflects real collaboration: a rowing team trying to win a race. It’s collaborative and team-based because they share a common goal and achieve it together. And not only that: if one of them started rowing in the opposite direction, the team would start going in circles.

The resources utilization trap.

Why do I consider it the hardest eXtreme Programming practice?

To do pair programming strictly, you need a strong set of soft skills. That includes good communication: effective, assertive, empathetic, direct, non-violent, and clear. It also requires solid feedback skills: knowing how to give it, when to give it, how to turn it into actions, and how to give feedback to yourself.

On top of that, doing it well means having the courage to say what you think in the moment, and respect: for yourself, for your partner, for the work you’re doing, and for the company you work for. It also requires discipline and the awareness that you’re working toward a shared objective.

A lot of the time these skills, principles, and values get ignored, which ends up creating sessions where two people get together to talk about a topic, or sometimes not even that, and they’re on the same call doing different things.

That’s why there are so many antipatterns in pair programming. Antipatterns are simply behaviors that are often shaped by everything mentioned above.

Probably the most important one is discipline, because it’s a key point for pair programming to work properly.

I think one reason pair programming is the hardest eXtreme Programming practice is that most people still think programming is something you do alone, where each person picks a task and owns it. That mindset shift is a big deal for many people in the industry.

Also, to do pair programming well, you need to be able to practice disagree & commit about opinions or ideas we might have, and be pragmatic. And in software, that can be really hard sometimes.

Why use it?

The real value: it’s a continuous, synchronous code review. Instead of waiting until the end, quality gets injected while the code is being created.

Continuous flow: by reviewing in real time, you remove waiting time. When the pair finishes the task, the code is already reviewed and approved, enabling real Continuous Integration (direct confirmation into the main branch).

Short feedback loops

One of the biggest benefits of pair programming is getting feedback cycles measured in seconds. You’re constantly talking to your teammate and considering things that, otherwise, you’d only catch once a pull request comes in and you’re asked to make changes.

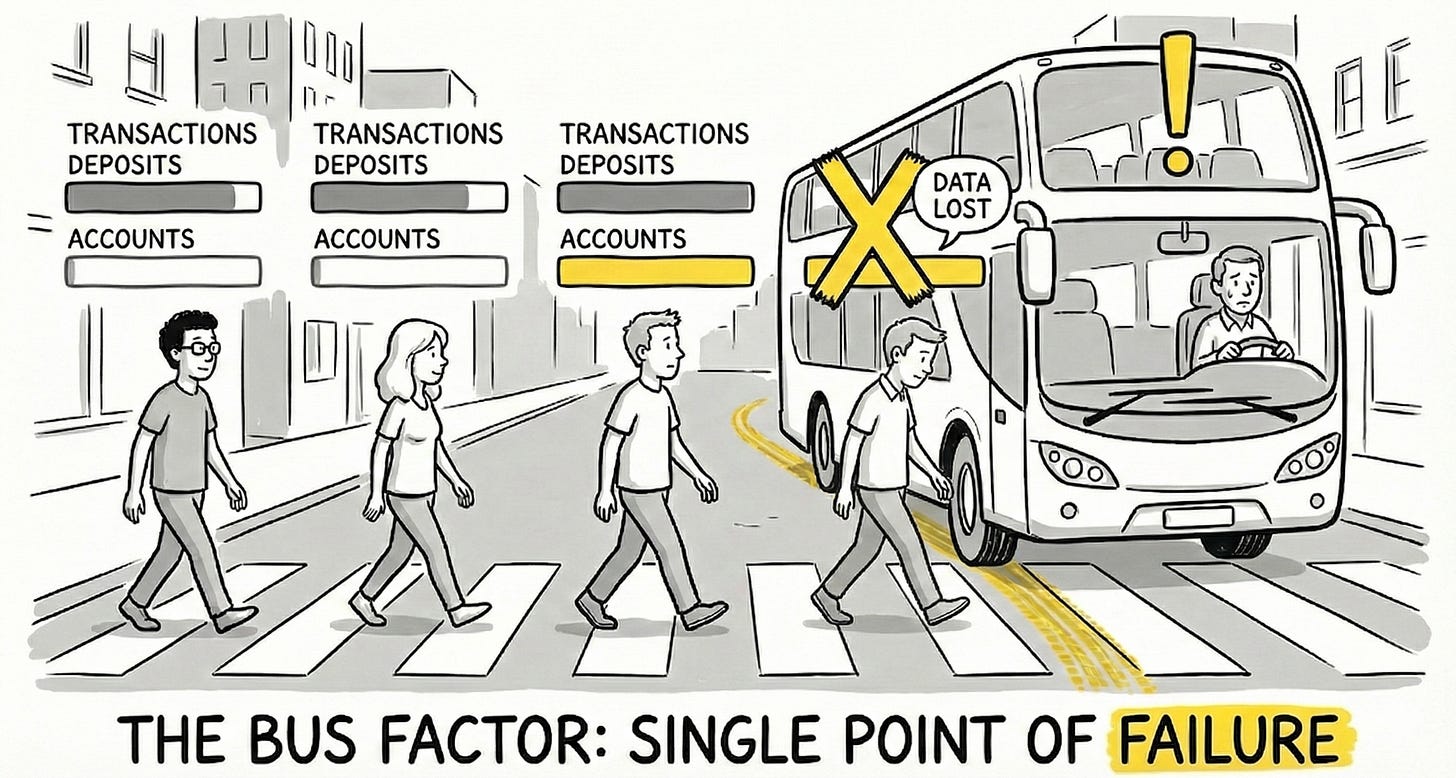

Bus Factor

Having critical areas of the system that only one person deeply understands is a huge financial liability. What’s the opportunity cost if that expert leaves the company?

The continuity advantage (vacations and leave):

With pair programming and pair rotation, knowledge spreads organically. This allows any team member to take vacation, sick leave, or handle a personal emergency without the project stopping. Work keeps moving because there’s always someone else who knows the context and can continue the task or guide a new teammate. This removes the “indispensable hero” stress and keeps the business operational.

Learning

Pair programming has a very important factor: it tries to ensure a more even distribution of knowledge. To achieve this, teams use things like pairing matrices and other strategies. That’s why pair programming doesn’t just distribute knowledge; by working with different teammates, with different strengths, and collaborating, everyone learns different ways of working.

This also matters because we don’t all have the same knowledge, and rotating with teammates lets us learn from others faster than trying to learn everything on our own.

Onboarding

How much does it cost a company to have a new developer be unproductive for their first three months? Getting a new team member into pair programming as early as possible is one of the fastest and most effective ways to transfer knowledge, shrinking time-to-value from months to weeks. But not every “pair” counts: getting on a call to chat is not pair programming. You need to know how to do it and choose the right style for the situation you’re in.

The economic argument: dismantling the cost myth

The main obstacle to adopting pair programming is a simplistic and wrong equation: “Paying two people sitting at one computer equals doubling development cost.” This view incorrectly assumes the main cost of software is the time developers spend typing code.

The economic reality of software development is very different:

The irrelevant cost of writing: the time spent writing the first version of the code is a tiny fraction of the software lifecycle.

The real hidden costs: the massive spend comes from:

Debugging: time spent finding and fixing bugs after code has been written.

Rework: rewriting code because requirements were misunderstood or the initial design was weak.

Maintenance: the effort to understand and modify complex code written by others in the past.

Wait time: time code sits idle waiting for review, testing, or deployment.

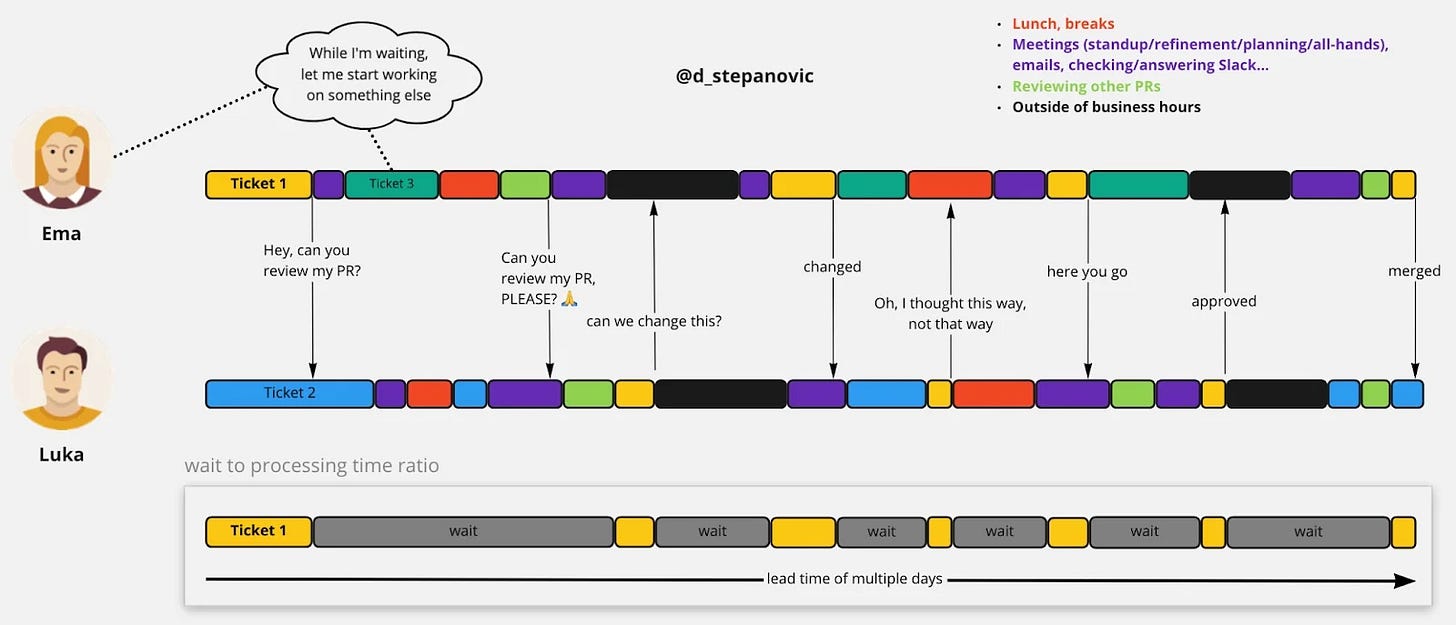

Pair Programming vs async Pull Requests

The traditional workflow based on async pull requests

Write Code → Open Pull Request → Wait for Review → Receive Comments → Fix → Merge

Is economically inefficient by design, as shown in analyses by experts like Dragan Stepanović:

The massive cost of inventory and waiting: in the traditional model, code spends most of its time “waiting”. In Lean terms, that stopped inventory is waste. It’s salary capital that’s not creating value for the end user.

The productivity killer: context switching: when a developer opens a pull request and has to wait, they start another task. When review comments arrive hours or days later, they have to stop what they’re doing and reload the previous context. Each context switch carries a heavy cognitive toll that destroys real productivity.

How to do it?

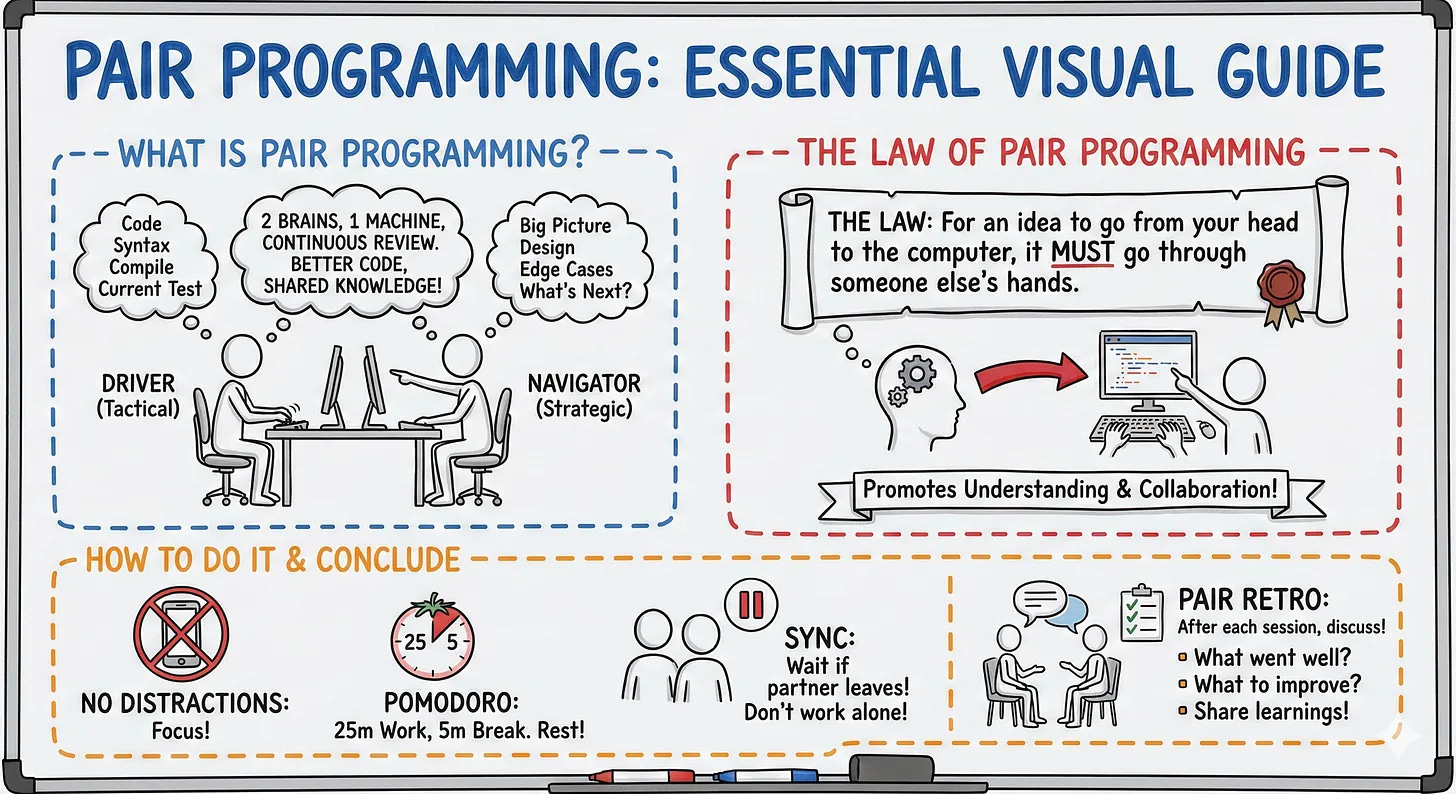

The Law

A rule of thumb popularized by experts like Llewellyn Falco:

For an idea to go from your head to the computer, it must pass through another person’s hands.

- Llewellyn Falco

If you’re the expert and you have a brilliant idea, don’t grab the keyboard. Tell your partner so they implement it. This ensures the idea was communicated and understood correctly.

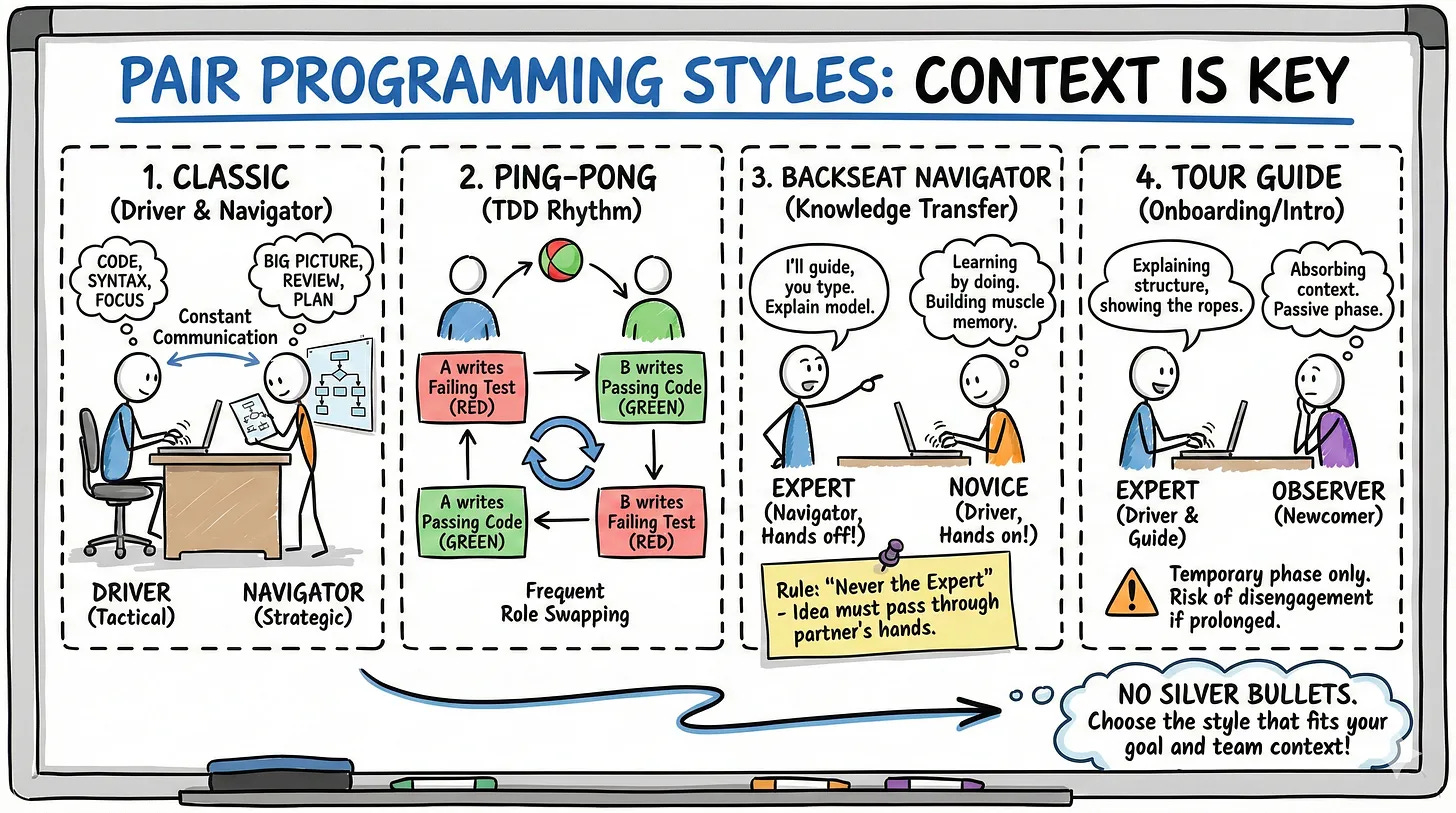

Styles

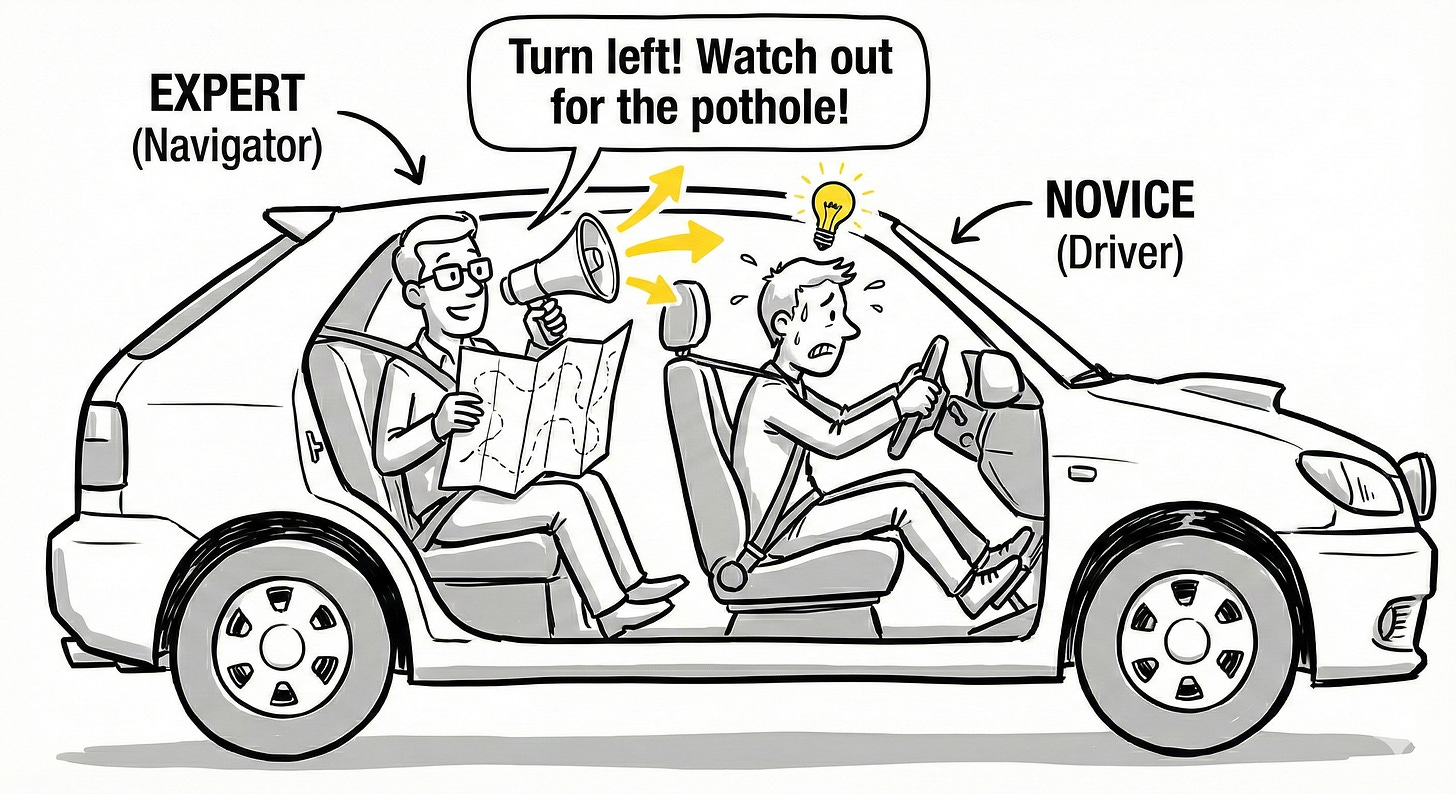

For pair programming to really work, you need to understand the core roles. I like explaining it with a rally metaphor.

On one side you have the Driver. This is the person controlling the keyboard and mouse. Their focus is tactical: syntax, writing the current test, and keeping the code compiling.

On the other side you have the Navigator. This person doesn’t touch the keyboard. Their focus is strategic: the big picture, edge cases, architecture, and anticipating logical mistakes.

From there, what matters is choosing the right style based on the task and the pair’s relative experience.

In pair programming there isn’t a single “correct” style. What matters is understanding what dynamic you’re creating and choosing the style based on the goal of the session: learning, moving fast, staying focused, or solving day-to-day problems.

“Backseat Navigator”

This style is often linked to the “never the expert” idea, and it works especially well when the goal is knowledge transfer.

The dynamic is simple: the expert, even if they know the solution, doesn’t touch the keyboard. They guide verbally, while the less experienced person drives.

Why does it work? Because it forces both to stay active: the expert must verbalize their mental model, and the novice must understand and execute. That creates real learning, not just “following steps”.

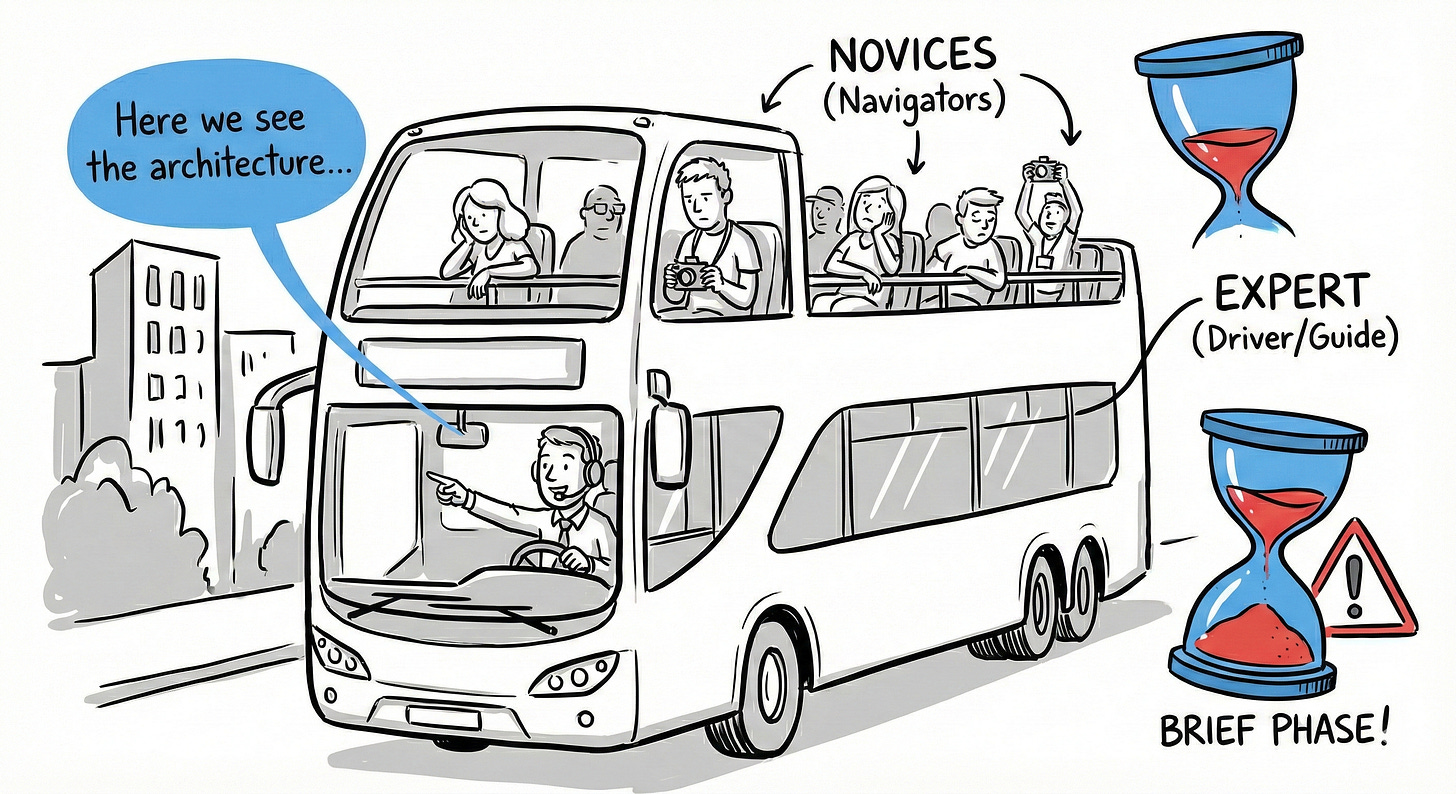

“Tour Guide”

This style is useful, but in a very specific context.

Here, the driver (usually the expert) writes and explains what they see and what they’re doing, while the navigator observes.

It fits onboarding and handovers, but with one important condition: it should be a short phase. If it drags on, it’s easy for the observer to disconnect.

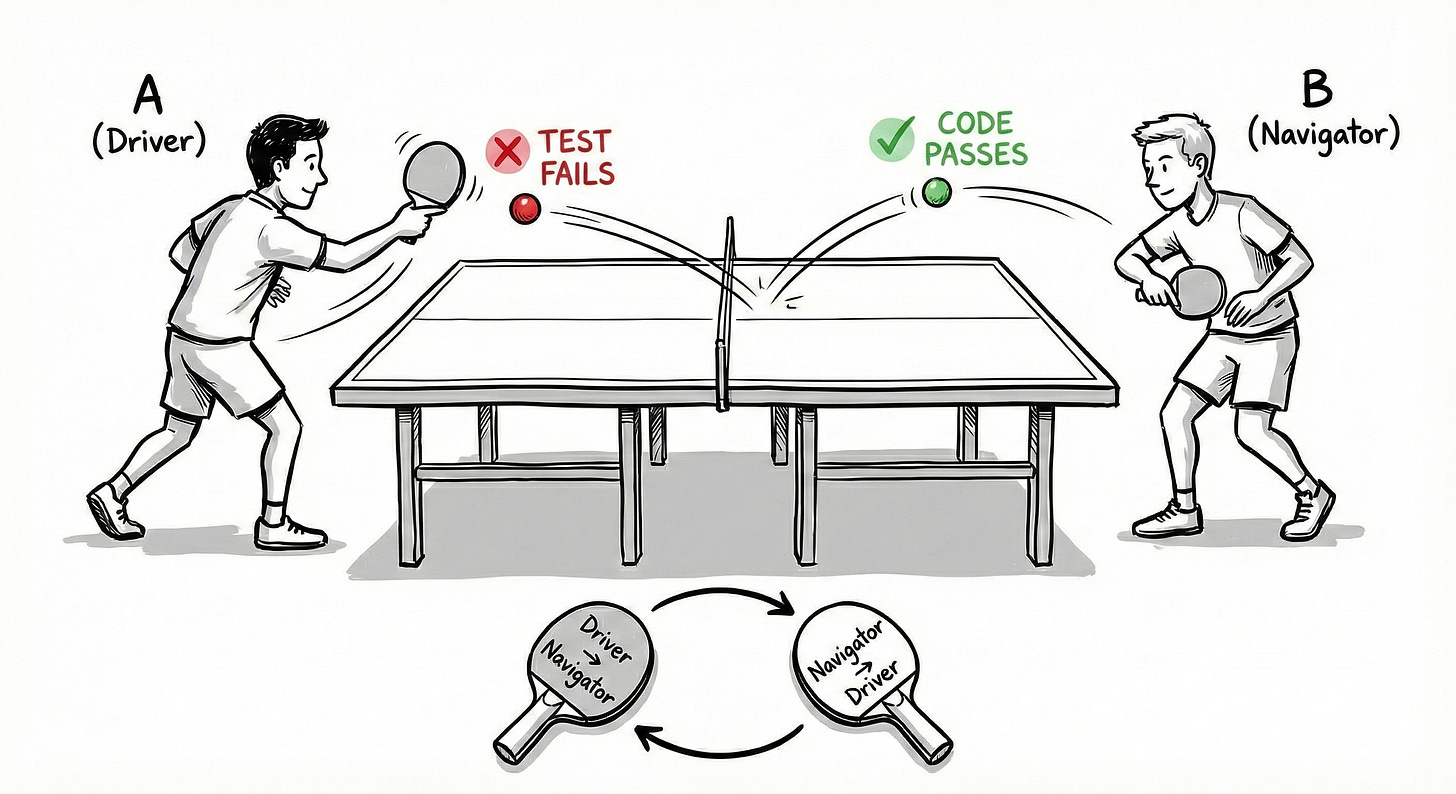

“Ping-Pong” (the TDD rhythm)

This style is great for keeping energy high and staying focused, especially when working with Test Driven Development.

It works in turns: one person writes a failing test; the other writes the minimum code to make it pass and then writes the next failing test. Then they switch again. All of this while keeping the Driver/Navigator mindset on each turn.

Classic (Driver and Navigator)

This is the most common format: a constant dialogue between the tactical role and the strategic role. One writes and executes, the other reviews, anticipates issues, thinks about edge cases, and helps keep direction.

It tends to work well for day-to-day work, especially when both people have similar levels. It can also work with different levels, although pairing two very inexperienced people is usually discouraged. Still, there are ways to manage and mitigate that when you do it intentionally.

Time management

Time management is key in this practice because we’re two people working toward a shared objective, so we should stay focused most of the time.

This creates fatigue, and the brain, unlike other muscles, takes a long time to recover when it’s tired. That’s why techniques like Pomodoro are recommended: 25 minutes of active work, 5 minutes of rest, and on the third iteration a longer break.

As professionals, we have to learn to manage this. It’s not only about fatigue; it can also be used to refocus a session when one person is losing focus.

How would that look? Let’s say a teammate is turning into the “philosophical pair”, drifting off and we’re not moving forward. I can suggest switching from 25-minute pomodoros to 10-minute ones, with 2- or 3-minute breaks. That forces more rotations and, most importantly, makes it harder for someone to ramble.

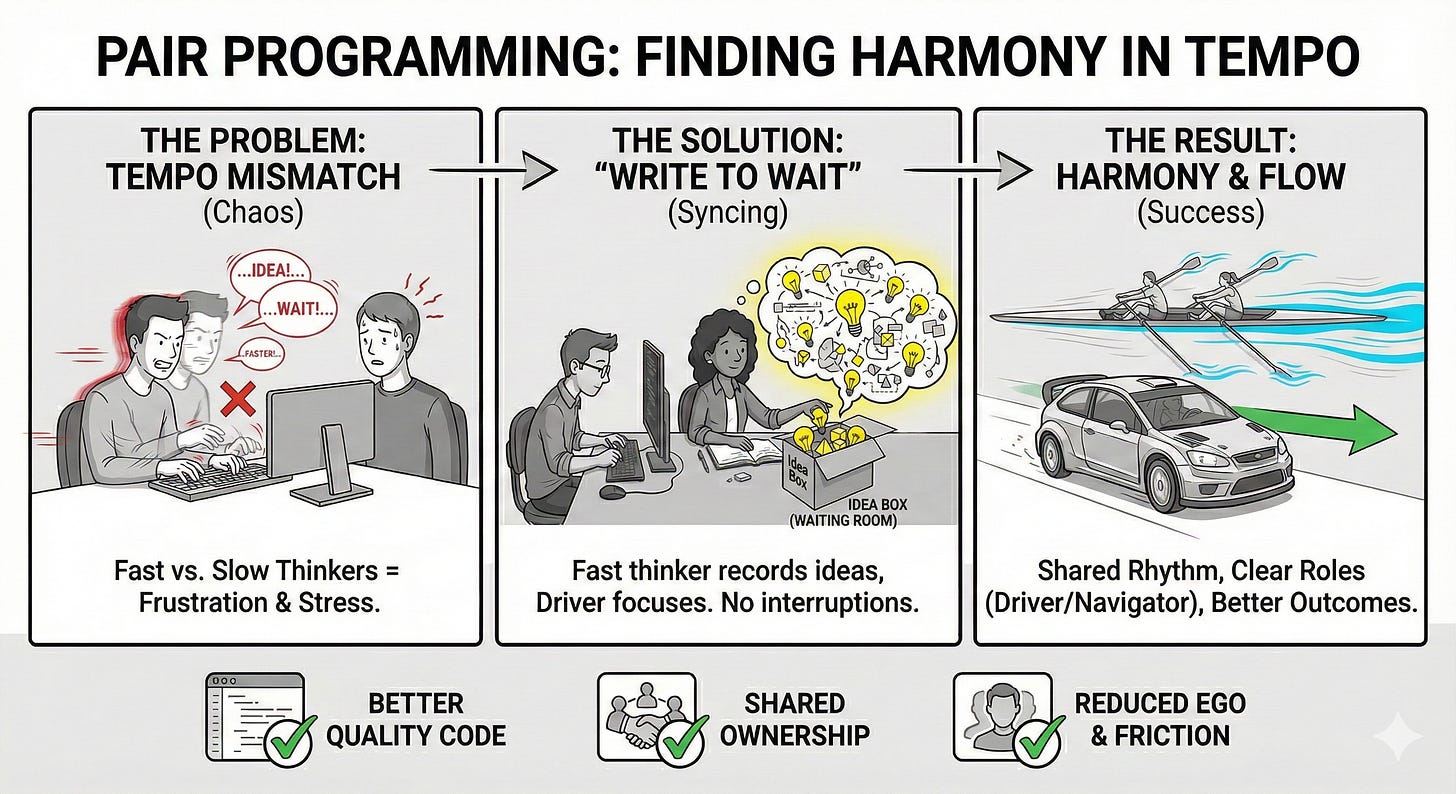

Tempo and pair harmony

After many hours of pairing, I’ve noticed something that matters as much as breaks: pacing.

I use the word tempo to describe the natural rhythm each person has while thinking and working. Some people have a fast tempo. They process and jump to solutions quickly. Others have a slower tempo. They need more time to reason, validate, and feel confident. Neither is better or worse.

What matters is finding harmony. The balance between both tempos.

If a fast-tempo person pairs with a slow-tempo person and the pace isn’t managed, the slow-tempo person usually pays the price. They can end the session exhausted, overwhelmed, or stressed, especially if they’re constantly trying to keep up.

Because of that, my rule of thumb is simple. When tempos differ, the fast-tempo person should be the one to slow down. The cost of slowing down is usually smaller, and it’s also a good way to practice patience, clarity, and better communication.

A practical technique that helps: if you have a fast tempo and your mind is already several steps ahead, write down your ideas on paper or in a notes document instead of saying them immediately. Then choose when and how to introduce them, preferably at natural checkpoints. For example, after a test, after a small refactor, or when the driver asks for input. This keeps the session calm, reduces pressure, and helps both people stay engaged.

Rotation

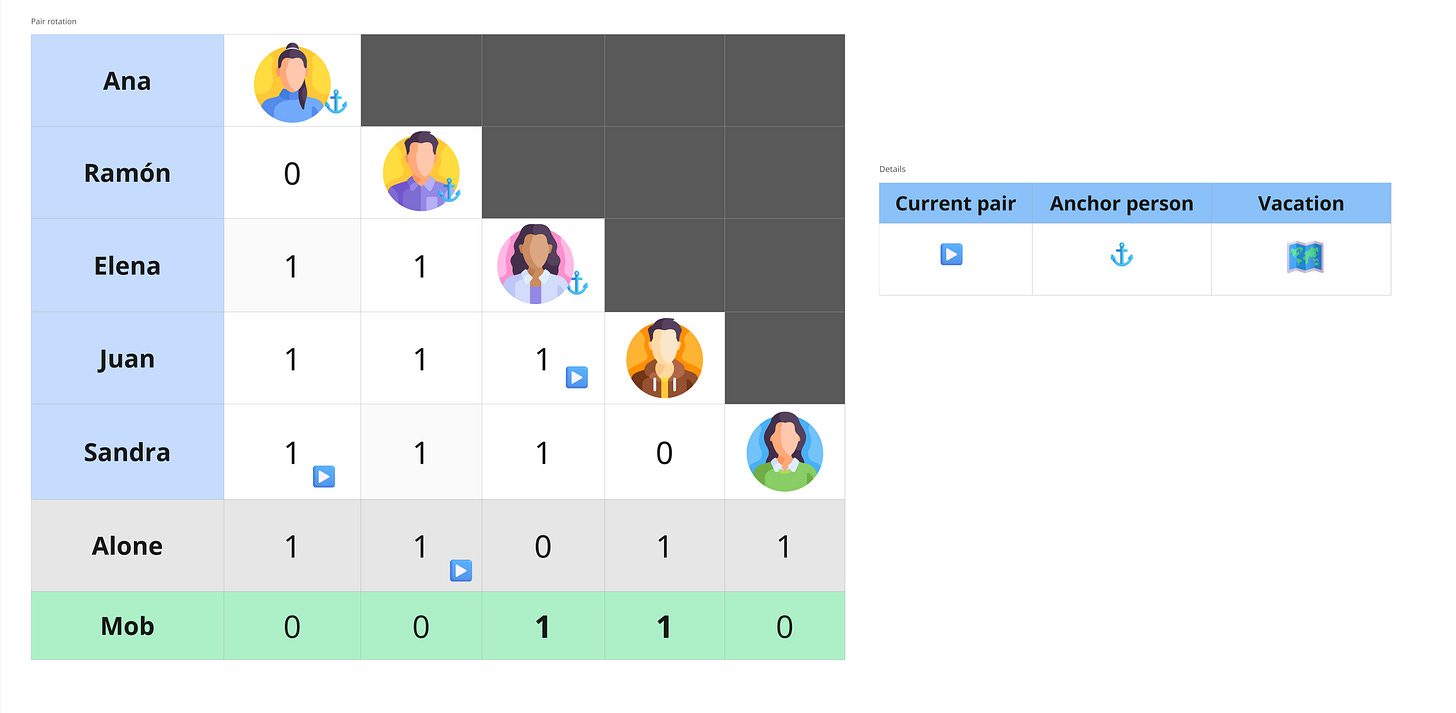

One of the most common mistakes when implementing pair programming is allowing pairs to never change. That creates two-person knowledge silos and excludes the rest of the team. To avoid that, teams use a visual and statistical tool: the Pairing Matrix.

What is the Pairing Matrix?

It’s a simple table where the names of all team members appear both in rows and columns.

How does rotation work?

First you decide how often you rotate. If the team hasn’t rotated much before, you usually start with less frequent rotations, for example once per iteration. Over time you try to shorten that interval so knowledge transfer happens across the team’s real tasks. In highly cohesive teams this can become daily rotation, where each day you rotate with a different teammate.

During rotation, you share the tasks currently in progress and the pairing matrix on screen. Considering current tasks, the team’s skills, and who has paired with whom, you decide the new pairs. You typically prioritize people who have paired less together, but it depends on context. What you want to avoid is having people who never pair with each other, since the goal is a more even knowledge distribution.

Each time a full pair starts a rotation, you increment the counter by +1 in the cell where their names intersect, and you mark which pair is currently working together.

There’s an important role in rotation: the anchor, the person responsible for transferring the context of an unfinished task to the next pair. This matters a lot: they need to explain the problem, the direction of the solution, and the “why”, and they need to communicate effectively. Otherwise, the handoff can take too long.

The shorter the rotation interval, the less context the anchor has to transfer, which makes it easier.

The anchor role also rotates. In other words, you try not to keep the same person as the anchor for task X across multiple rotations.

Strategic benefits of the matrix

Reduced Bus Factor: it mathematically guarantees that, over time, everyone has worked with everyone. System knowledge becomes more evenly spread.

Early detection of interpersonal conflicts: if a leader notices a specific cell stays at zero or very low despite opportunities, it can be an early signal of relationship issues or technical incompatibility between two members, enabling early intervention.

Integrating juniors or less experienced people: it prevents junior profiles from always pairing with the same senior, exposing them to different ways of thinking and solving problems.

What does a session look like?

Preparation

Goal defined (what are we solving, and what’s the current state)

Check calendars (align on breaks and availability). It’s important to agree what to do while the pair is split before switching to another meeting or separating.

Understand the task (raise your hand if unclear)

Style selected (Driver-Nav / Ping-Pong / Strong)

Roles assigned (who starts driving?)

Audio/Video check passed

Align on tempo (pace) and agree on a signal to slow down or pause

Timebox and breaks agreed (e.g., 25/5)

Backup channel ready (Teams or a work room)

Execution

Driver is “thinking aloud”

Fast-thinkers capture ideas in notes and share them at checkpoints, not mid-flow.

Navigator is taking notes and spotting risks

Notifications silenced

Roles switched at least once

No “Ghost Mode” (both vocal)

Warning: watch out for camera-driven visual fatigue, also known as Zoom fatigue. Cameras can help with non-verbal feedback, so there are pros and cons.

Wrap-up

Tests green / WIP marked

Both understand the problem space and the solution space

Next steps clear

Mini-retro: things to improve from the pairing and 1:1 feedback

Share any key insights with the team when needed

What would a learning session look like in an unfamiliar context?

Assumption: only code exists (no documentation)

In this case, the pair explores the code together from the start, using “code archaeology” techniques with the Driver/Navigator style, documenting as they learn how things work. The output can be documentation and diagrams of how the application works; in other words, the output is context and knowledge. This assumes you don’t need to introduce changes yet; you’re inheriting the codebase or doing a handover (not ideal, but it happens).

These sessions can be together or split. You can decide whether you’ll look at the same part of the code or different parts, and set a research timebox, for example a pomodoro: split the pair for individual work during that time. For example, agree that each person will explore a different part of the code for 25 minutes, take a 5-minute break, and then in the next 25 minutes one explains to the other what they understood. You align on it and document it to share with the team.

Once documentation exists, you can transfer knowledge to the rest of the team. You could also run a mob/ensemble session to share knowledge in a more practical way and, if there are areas without tests, try adding some tests to resolve doubts and reduce fear of the unknown.

If the inherited code belongs to a team that still exists in the company, you can collect questions from the ensemble/mob and ask them to get the maximum possible context.

Antipatterns

As I mentioned at the beginning, when I talked about why pair programming is hard, I brought up antipatterns, but I didn’t go into detail about what I meant. Now I’ll give some examples, but there are more. Antipatterns are behaviors that impact the pair, and there can be many. These are just a few.

The silent partner: the teammate who’s on the call (you know because you saw them join) but doesn’t actively participate, even when it’s their turn to drive.

The solo act: someone who, even after agreeing on something, does whatever they want and ignores the agreements. Also known as the cowboy.

Distracted pair: the teammate who’s looking at their phone or otherwise distracted during the session, doing things that are not working toward the session goal.

The dictator: the person who dictates how things must be done and won’t listen to reason.

The philosophical pair: the person who starts talking about deep topics and the importance of things that sometimes aren’t even what you’re looking at, and that hurts the pair’s focus.

The code war: when two teammates with strong opinions fight over their opinions instead of focusing on what matters. Sometimes it’s two dictators fighting each other.

Not everything is good

Well-executed pair programming is probably the most exhausting technique out there. Being constantly focused tires you out. That’s why you need time and break management techniques. It’s also why, sometimes, people recommend not doing it for a full 8-hour workday, because it can be too much.

It’s important to remember the brain handles fatigue differently. If the brain is exhausted, it blocks you from doing other things, and that can impact personal life. That was my case at the beginning. I did get used to it and learned to manage it better, but everyone is different. That’s why some places agree as a team to do between X hours and Y hours of pairing.

Conclusions

Even though pair programming is complex and a way of working that many companies don’t use, it’s proven to be one of the most effective tools in the scenarios discussed. From my point of view, it’s a very important tool to have in the toolbox of a CTO, Tech Lead, Team Lead, and even any developer.

References

Books:

Pair Programming Illuminated - Laurie Williams y Robert Kessler.

Practical Remote Pair Programming - Adrian Bolboacă.

Extreme Programming Explained: Embrace Change - Kent Beck.

The Pragmatic Programmer - Andrew Hunt y David Thomas.

Software Economics - Luis Artola.

Articles and webs:

On Pair Programming - Martin Fowler.

Promiscuous Pairing and Beginner’s Mind - Martin Fowler (Fuente clave sobre matrices de rotación).

Pair Programming Simplificado - Codurance.

VMware Tanzu: Pair Programming - VMware Tanzu Blog.

The Different Styles of Pair Programming - Drovio Blog.

Never the Expert: Breaking Knowledge Silos - Emmanuel Valverde Ramos.

Taks and Videos:

Pair Programming Anti Patterns - Digvijay Gunjal (ThoughtWorks).

Pair Programming: Fundamentos y aspectos clave - Fran (Codurance).

The Pros & Cons Of Pair Programming - Dave Farley.

Async Code Reviews Are Choking Your Company’s Throughput - Dragan Stepanović.

Really strong breakdown of why async PR workflows create so much waste. The tempo concept is something I hadnt seen formally articulated before but it's so true from experience, mismatched pacing absolutely kills productive pairing sessions. The pomodoro adjustment technique (switching from 25min to 10min when someone drifts) is pretty clever for handling the philosophical pair antipattern.