Building a skill matrix that actually helps your team

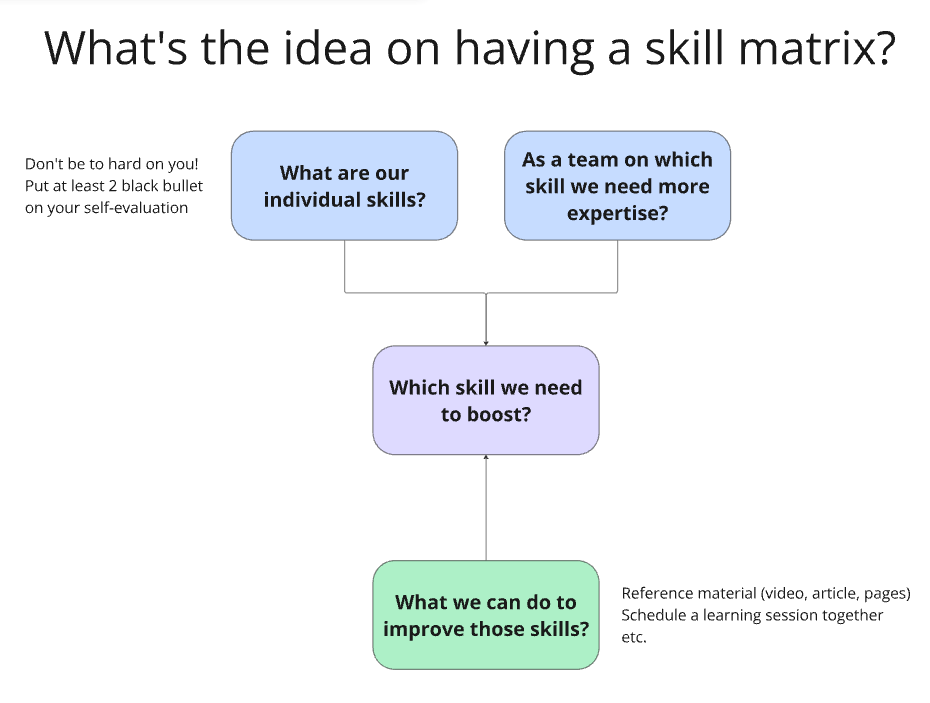

Most teams guess who knows what. This article shows how to use a skill matrix as a shared map of real capabilities, not a ranking, to guide training, hiring, initiatives and healthy growth.

Before anything else: this is not your career ladder

Let’s clear the biggest misunderstanding first.

A skill matrix is not automatically your career path, your performance review, or your salary justification. It can be connected to those things, but it does not have to be. And in many cases, it should not be.

Think of it like this:

A career path is about titles, compensation, and formal expectations over years.

A skill matrix is about the capabilities the team needs over the next months and quarters to do its job well.

You can run a very healthy, effective skill matrix process that has zero direct link to promotions or performance ratings. In that mode, it is a tool for:

Understanding the current capabilities of the team.

Understanding the capabilities the team will need.

Deciding how to get from here to there.

If you later decide to connect it to career paths, that is a separate design decision and needs a very explicit conversation with the team.

So when you introduce this, say it clearly, in plain words, more than once:

“This matrix is not your performance review and not your promotion checklist. It is a team tool to understand what we collectively know and what we need to learn.”

If at some point you do connect parts of the matrix to a career framework, you also owe the team a very explicit explanation of how and why so they do not feel tricked.

Keep that distinction in mind while you read the rest. It changes how you design, explain, and use the matrix.

Your team is a system, not a collection of CVs

Donella Meadows, in Thinking in Systems, talks about systems as things with feedback loops, delays, and interactions that are not obvious by looking at pieces in isolation. One of her most famous lines is:

“We can’t control systems or figure them out. But we can dance with them!” Goodreads

Your team is one of those systems.

You have:

People with overlapping skills and gaps.

A delivery process with feedback loops (incidents, reviews, metrics, customer feedback).

Constraints from the business, legacy systems, compliance, and platform choices.

Culture, trust levels, communication patterns, and habits.

A skill matrix, done well, is not “a table of who knows Kubernetes”. It is a lens on that system:

Where are the single points of failure? (Bus factor)

Where are reinforcing loops? (“Only one person knows X, so they get all the work, so nobody else learns it.”)

Where are we investing in capabilities that the organization does not really value?

Where are we under-investing in skills that our strategy depends on?

If you see the matrix as a living artifact inside a living system, you stop treating it as a static HR spreadsheet and start using it as a feedback tool.

Three guiding questions: now, near future, and should-be future

Every useful skill matrix is trying to answer three questions at the same time:

Where are we now?

What skills exist in the team today, at what depth, and how spread are they?Where do we think we are going?

What the team wants to do: ambitions, interests, the product roadmap that is already visible, technologies we realistically plan to adopt.Where do we need to go to align with the organization?

What the company strategy implies we should be good at, even if people are not naturally moving there.

This is where your AS-IS / TO-BE sessions fit:

AS-IS: you make explicit the history, the decisions, and the current reality. This is not just technical; it is also “we always ship in a rush” or “we do not have anyone who really understands observability”.

TO-BE: you explore three overlapping views:

What the company wants from this team.

What the company actually needs, given strategy, market, and constraints.

What the team members want and need for their own growth.

The tension between those three is exactly where the matrix becomes interesting. You want to design it in a way that reflects all three lenses and then revisit it regularly, not once every few years.

High level design of the matrix: sections that reflect reality

Let’s go through the sections one by one, with depth and intent.

Organization-level foundations

This is where you list the non-negotiable hard things: the tech stack and constraints the organization has chosen.

Examples:

Primary languages and frameworks.

Cloud provider and main infra tools.

Observability stack.

Security and compliance basics that apply to everyone.

Coding standards and architecture decisions that are not up for debate.

This section is not about preference. It is about acknowledging that the system already made choices, and people must be able to operate inside them.

As a leader, you are answering: “What does somebody joining this team need to be able to work safely and effectively in this environment?”

Basics: things everyone in the technical track should know

This is your floor, not your ceiling.

Typical entries:

Version control (Git, branching, code review).

Basic SQL and data querying.

Containers and basic Docker usage.

How your build system works.

Basic debugging practices.

Core security hygiene (secrets, auth, least privilege at a basic level).

You are not trying to turn everyone into a database expert. You are saying: “To call yourself an engineer in this team, you need at least this level of autonomy.”

The Pragmatic Programmer by Andrew Hunt and David Thomas pushes a mindset of responsibility, continuous learning, and paying attention to the “broken windows” in your codebase.

Your basics section should reflect that spirit: fewer shiny tools, more fundamentals that make people reliable under pressure.

Ways of working

This is about how you work, not the tools.

Drawing from XP practices and books you might capture skills like:

Working in small, vertical slices instead of big-bang features.

Pair or mob programming, when and how to use it.

Test-driven development and refactoring.

Effective planning in iterations, including honest estimates and reshaping scope.

How you handle on-call, incidents, and postmortems.

How you collaborate with Product and Design.

This is where you make explicit the real way of working you want, not the slideware version.

If you say “we do continuous delivery” but nobody in the team can safely release multiple times per day, the matrix should expose that gap.

Cross-cutting technical skills

Here you put engineering skills that sit on top of the basics and are not tied to a single technology:

Principles of software design: cohesion, coupling, boundaries, modularity.

Techniques for refactoring large codebases.

Working safely with legacy systems.

Architecture thinking: trade-offs, patterns, and knowing when “good enough” is actually good enough.

Observability and diagnostics.

Performance analysis.

Books like The Pragmatic Programmer and Extreme Programming Explored push you to think about design as a continuous activity, not a one-off diagram. Artifacts like architecture decision records and evolutionary design can live in this section.

As a Staff or Principal engineer, this section is where you pay a lot of attention. This is where “technical leverage” lives.

Domain knowledge

This is about the business and problem space:

Concepts, entities, and workflows in your domain.

Critical invariants and constraints (“this number must always reconcile with financial system X”).

Regulations or rules that heavily shape your system.

Knowledge of upstream and downstream systems.

You can break this down by subdomain. Domain Driven Design language can help here, but you do not need to be formal to be useful.

The traps you avoid here:

Only one person who “really understands billing”.

Only one person who “really understands the data model”.

Nobody understanding why a weird workaround exists.

Soft skills and why they are not “nice to have”

You listed a set of soft skills that you personally consider important. Let’s make them concrete, This are some I like to use, but this will depend on your context and the culture of your team (to know more about this read the cultural map).

Communication

Effective: clear, concise, and geared towards decisions and action.

Assertive: able to say “no” or “not now” in a respectful way.

Non violent: owning your feelings and observations, not attacking the person.

Empathic: tuned to how the other person might hear what you are saying.

Adapted to the listener: how you explain an incident to an SRE is not how you explain it to a PM.

Effective communication is key.

Feedback

Giving it in a way that is specific, timely, and focused on behaviour and impact.

Receiving it even when it is clumsy or poorly delivered, without shutting down.

Acting on it instead of collecting feedback like stickers.

Being able to reflect and give feedback to yourself.

This aligns with modern leadership work on “soft skilled leadership” where gentle but clear feedback is a core mechanism for learning and trust, not punishment.

Pragmatism

Finding workable middle ground that serves the team and the product, not your ego.

Understanding when to push for quality and when to accept “good enough” for now.

Being aware of software economics: cost, time, quality, and risk trade-offs.

This is where Software Engineering Economics by Barry Boehm is useful in the background: it frames decisions as economic trade-offs instead of moral fights.

Disagree and commit

Being able to say:

“I still think my approach is better, but we made a decision. I will help make this one succeed and we can revisit if reality proves us wrong.”

Accountability and extreme ownership

From Extreme Ownership you can borrow a compact idea:

“No bad teams, only bad leaders.”

In a skill matrix, this translates into:

Owning your gaps instead of hiding them.

Owning your impact on the team’s capabilities.

Owning your part when the system fails, even if it was “not your code”.

This does not mean blaming yourself for everything. It means you look first at what you could do differently, which simplifies problem solving and reduces blame games.

Respect

For yourself: not accepting impossible workloads or unsafe expectations.

For your colleagues: assuming competence and good intent, even when you disagree.

For your work: caring about the quality of what you deliver, but not fetishizing perfection.

You cannot control everything, but you can control how you respond, how disciplined you are, and whether you respect yourself enough to act according to your values instead of impulse.

Simplicity

Being able to remove, not only add.

Preferring clear, boring solutions over clever, opaque ones.

Explaining complex things in language that juniors and stakeholders can follow.

Continuous improvement

Looking at yourself and your team as something that can evolve deliberately.

Using retrospectives, postmortems, and 1:1s as real learning tools.

Avoiding the “boiled frog” effect where things slowly degrade because nobody stops to notice.

Software economics

Understanding that quality, speed, cost, and scope, managing risks, an leverage this with adding value to the customers.

Being able to reason about the economic impact of technical decisions: build vs buy, quick hacks vs sustainable change, technical debt versus opportunity cost.

This might be a separate section in your matrix, or part of pragmatism and technical decision making. For Staff and Principal roles, this is non optional.

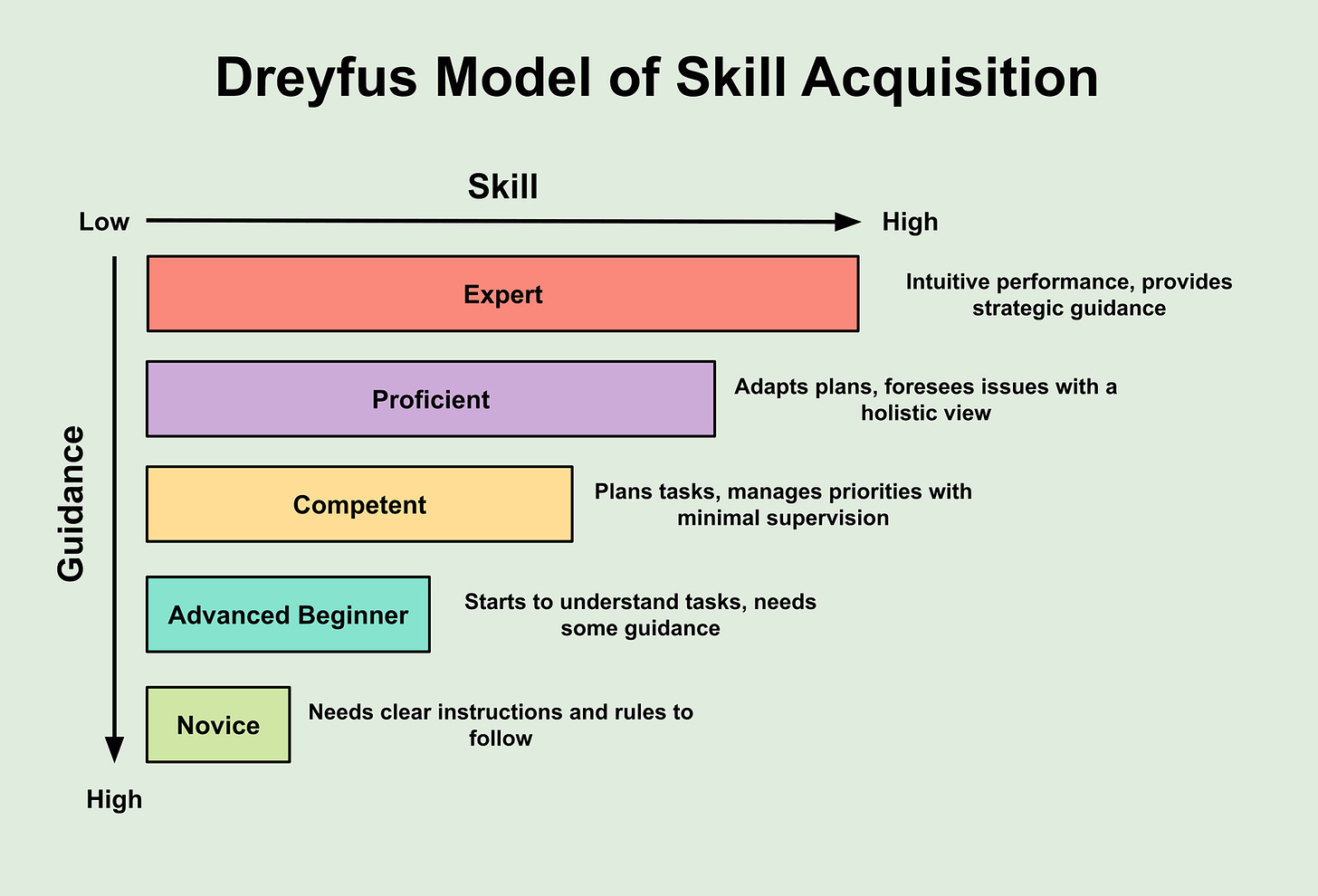

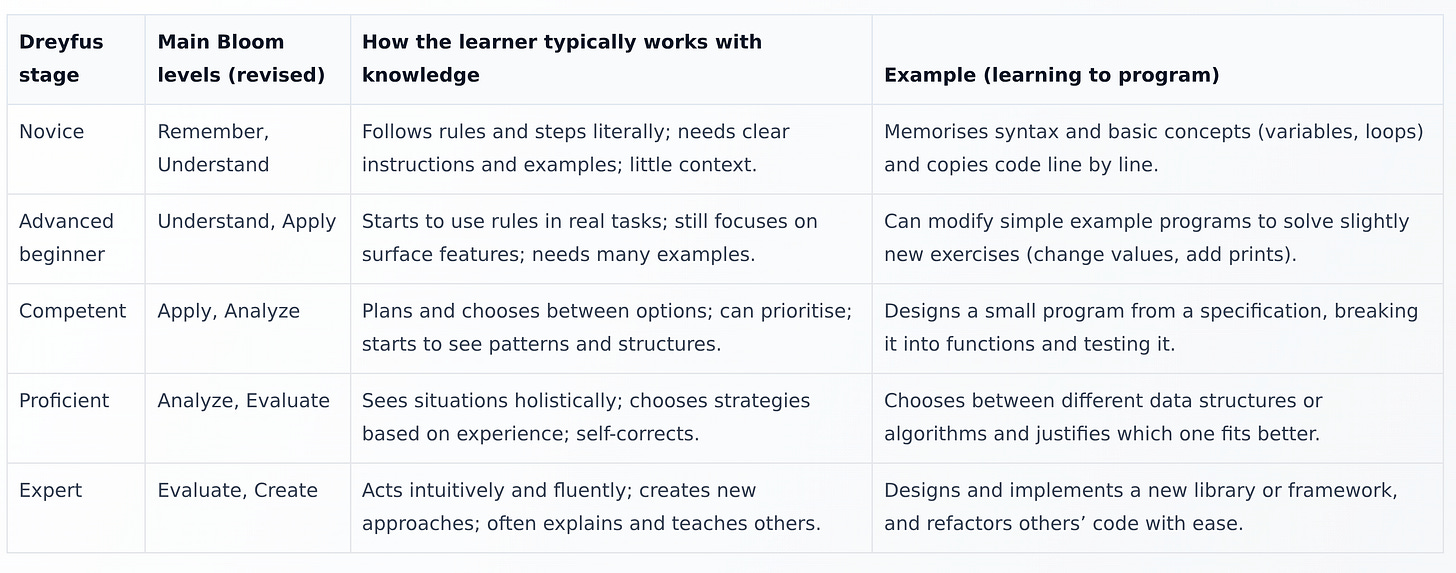

Levels: combining Dreyfus and Bloom without turning people into numbers

You mentioned using the Dreyfus model and Bloom’s taxonomy. That is a very solid foundation, if you use them with care.

Dreyfus: how people actually grow skills

The Dreyfus model describes stages like novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert.

In practice, for a skill matrix, that might look like:

Novice: needs step by step instructions and supervision.

Advanced beginner: can perform simple tasks independently but struggles when things diverge from the “happy path”.

Competent: can plan, make trade-offs, and deliver outcomes in this area with some guidance.

Proficient: sees patterns, anticipates problems, mentors others, and adapts flexibly.

Expert: shapes how the team and organization think about this area.

The key is that Dreyfus is about behaviour in context, not about how many books you read.

Bloom: what kind of thinking is involved

Bloom’s taxonomy, especially the revised version, describes cognitive levels like Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, and Create.

Combined with Dreyfus, it lets you express levels in terms of what someone can actually do:

For example, for “Refactoring legacy code safely”:

Level 1 (novice / remember): can describe what refactoring is and list common techniques.

Level 2 (advanced beginner / understand apply): can use basic refactoring techniques when guided or on low risk code.

Level 3 (competent / analyze): can analyze legacy code, propose refactorings, and execute them with tests and review.

Level 4 (proficient / evaluate): can evaluate different refactoring strategies, balance risk and benefit, and lead others through the work.

Level 5 (expert / create): can design migration strategies for large legacy systems and evolve architecture over time.

This makes the matrix feel concrete and fairer. You are not saying “3 out of 5” without context; you are saying “can do X, Y, Z reliably at this level of autonomy”.

Explaining these models to the team

Do not hide Dreyfus and Bloom behind jargon. Take time to explain, with examples from your own context, how skill growth actually looks.

You can literally draw a few examples:

“Novice in Kubernetes” in your stack versus “proficient in Kubernetes” and what that looks like day to day.

“Competent in giving feedback” versus “expert in giving feedback”.

The goal is that people can self calibrate and also understand how to give fair evaluations to others.

How to evaluate: choosing a process that fits trust and maturity

You outlined two modes, and they map nicely to team maturity and psychological safety.

High trust teams: peers evaluate, then calibrate

For teams with strong trust and a culture of open feedback:

Each person is evaluated by their peers, not by themselves.

Peers bring multiple perspectives and catch blind spots and biases.

After that, there is a calibration session with the Tech Lead or Manager where disagreements and nuances are discussed.

This can produce very rich conversations:

“Why do you see me as more advanced here than I do?”

“What behaviours made you rate yourself higher than others did?”

If you take an Extreme Ownership mindset seriously as a leader, you treat surprising evaluations as signals about your own communication, expectations, and support systems, not as reasons to punish the team.

Lower trust or newer teams: self evaluation plus calibration

For less mature teams, or environments where trust is fragile:

Everyone fills a survey and evaluates themselves on the matrix.

Then each person has a calibration 1:1 with the Tech Lead or Manager.

This mode demands a lot more preparation from the leader:

You need clear behavioural descriptions for each level.

You need examples ready to back up your perspective.

You need coaching skills to avoid the conversation turning into “you are wrong, I am right”.

Good soft skills are critical here: non violent communication, active listening, and staying grounded in shared reality.

In all cases: repeat and integrate into your rhythm

A one off skill matrix exercise is better than nothing, but the real power comes when you:

Revisit it periodically (for example yearly or aligned with major initiative shifts).

Use it before starting big initiatives to ask “do we actually have the skills needed for this?”

Use it in planning conversations with Product to shape roadmaps around realistic capability growth.

This is systems thinking again: you want the matrix to be part of a feedback loop where learnings from delivery feed into capability planning, which feeds back into how you design work.

What you do after the matrix matters more than the matrix itself

Once you have a filled matrix, the real work starts.

Planning training and upskilling

With the matrix, you and the team can see:

Gaps that are critical for upcoming initiatives.

Overloaded experts who need to be cloned.

People whose interests line up with upcoming work.

Then you can design:

Internal training sessions led by team members with higher levels in a skill.

Pairing plans (who pairs with whom on which tasks).

External courses or coaching where internal expertise is missing.

Space in the roadmap for learning oriented work, not just feature delivery.

This is where DevOps and Agile literature like Accelerate and The Art of Agile Development are useful in the background: they emphasize that investing in capabilities like test automation, trunk-based development, and cross-functional collaboration pays off in delivery performance.

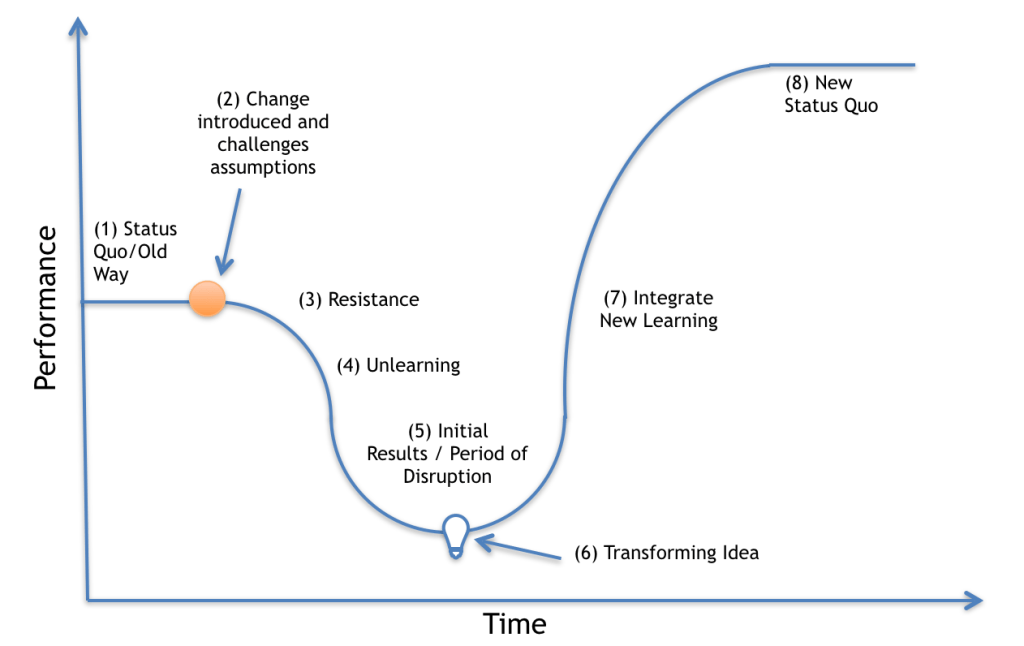

Using 1:1s to support individuals

The matrix gives structure to 1:1s:

You can help people choose one or two skills to focus on for the next period.

You can suggest realistic actions: projects, pairings, reading, mentoring.

You can redirect them to others in the team who are stronger in an area.

Important point: you as a Tech Lead or Manager are not always the best person to teach everything. Sometimes your best move is to connect people with the right peer or external resource and then get out of the way.

As Tech Lead/Managers we also have to take into consideration the J curve, at the time of suggestion actions.

Aligning with initiative planning and software economics

From a software economics perspective, you want to avoid:

Starting a critical initiative that depends on a skill only one person has.

Creating roadmaps that assume skills appear by magic.

Burning people out by always putting the same experts on the critical path.

The matrix is the factual basis you can bring into planning discussions with Product and other stakeholders:

“We have nobody at competent level in this area. If we want this in Q3, we need time and budget for training, pairing, or hiring.”

“We can do this faster if we invest here and simplify there.”

You are turning gut feeling into visible data.

Skill matrix and career path: deliberately decoupled, optionally connected

This deserves its own careful section.

Default posture: decoupled

By default, it is healthier to keep the skill matrix separate from your formal career ladder and performance evaluation.

Reasons:

People are more honest when they know this will not be used to judge their raise.

You avoid “gaming” the matrix to look ready for the next title.

You keep space for skills that are critical for the team but not easily recognized by standard titles.

You can still use the matrix in performance and career conversations, but not as a direct formula.

For example:

“You say you want to grow towards Staff Engineer. Let’s look at these skills that are important for that path and see where you are today.”

“You want to move towards a more product-heavy role; this part of the matrix becomes more relevant than that part.”

Your matrix should help people see what that kind of impact requires, without turning into a brittle “Staff engineer template”.

When you do connect them

There are situations where it makes sense to align parts of the matrix with career paths:

You have a formal competency framework and want concrete behavioural descriptions.

You want to make promotions more transparent by showing what “Senior” or “Staff” actually means in day to day skills.

You want to ensure that compensation matches responsibility and capability.

If you go this route:

Be explicit: “These rows are now officially linked to our career framework in this way.”

Be transparent about how they will be used in promotion and evaluation.

Be careful not to overfit: people should not feel that having one missing box blocks their entire progression if their impact is clear elsewhere.

Here, The Dichotomy of Leadership is relevant again: the balance between clear standards and flexible judgement is a real leadership tension. You want standards strong enough to guide behaviour, but flexible enough to account for context and different archetypes (Tech Lead vs Architect vs Solver vs Right Hand).

Communicating the boundary

Whatever you choose, over-communicate the boundary.

If the matrix is separate from performance: repeat that, and behave accordingly.

If some parts are connected: explain which parts and how.

Nothing kills trust faster than an artifact that is sold as “for your growth” and then quietly used as a promotion gate without discussion.

Systems thinking: watching for traps and leverage points

Returning to Meadows and systems, there are a few classic traps to watch for in skill matrices:

Shifting the burden: using hiring to patch every gap instead of growing people.

Success to the successful: always giving critical work to the same people, which makes them grow faster and others stagnate.

Goal fixation: optimizing for “good matrix scores” instead of better delivery and healthier culture.

And there are leverage points:

Changing information flows: making skills visible helps decisions about pairing, ownership, and risk.

Changing rules: for example “no initiative starts if it creates a new single point of failure in this skill”, Or you could apply never the expert.

Changing mindsets: from “I am my level” to “skills are things I can grow and share”.

You can also apply the “dance with systems” attitude: you will not design the perfect matrix first try. You experiment, look at feedback, and adapt.

How this feels from a junior engineer’s perspective

If you are earlier in your career, a skill matrix can look scary at first. Lots of rows, lots of levels, lots of things you “do not have yet”.

Here is what a healthy matrix should feel like for you:

A map, not a judgement. It shows what exists, where you are, and what paths are possible.

A conversation starter: “I want to grow in these areas, can we find opportunities?”

A safety mechanism: if the team uses it seriously, it prevents you from being thrown into work that requires skills you clearly do not have yet, without support.

Ryan Holiday puts it bluntly:

“There is nothing worth doing that is not scary.” Goodreads

A good skill matrix makes the scary stuff visible, gives you language for it, and then lets you approach it step by step instead of pretending everything is fine.

Putting it all together: a practical sequence for leaders

Here is a concrete flow you can follow as a Tech Lead, Team Lead, Staff or Principal:

Run AS-IS / TO-BE sessions

Capture current reality and history.

Explore what the company wants, what it needs, and what the team wants and needs.

Define your sections

Organization constraints, basics, ways of working, cross-cutting skills, domain, soft skills, economics.

For each, write a short “why this exists” statement.

Draft levels using Dreyfus and Bloom

For each skill, define behaviours for a small number of levels (for example 4 or 5).

Focus on observable behaviour and autonomy, not vague adjectives.

Socialize and refine with the team

Present the draft, explain the intent, and let people challenge it.

Adjust based on reality; do not design in isolation.

Decide and communicate how it relates to career paths

Make a conscious decision: decoupled, partially connected, or integrated.

Explain it clearly and check that people understood.

Choose your evaluation process

Peer evaluation plus calibration for high trust teams.

Self evaluation plus calibration for lower trust or newer teams.

In both cases, prepare your leaders and facilitators.

Run the evaluation and host calibration conversations

Take your time; this is not a form filling exercise.

Capture disagreements as learning, not as “problem employees”.

Turn results into actions

Plan training, pairing, hiring, and initiative sequencing based on real data.

Use the matrix in 1:1s to help people choose growth goals.

Revisit regularly and integrate into your system

Reassess when strategy or tech stack changes significantly.

Use the matrix as an input to planning, not an annual ceremony.

Throughout this, keep in mind a small quote from Thinking in Systems and a small quote from The Pragmatic Programmer:

“We can’t control systems or figure them out. But we can dance with them!” Goodreads

“Ask for forgiveness, not permission. Be a catalyst for change.” pragprog.com+3chrisdpadilla.com+3picture.iczhiku.com+3

A skill matrix is not a control panel. It is a way to see the dance more clearly so you can change your steps together.

References

These are the main books and authors that inform the ideas in this article:

Jocko Willink, Leif Babin, Extreme Ownership: How U.S. Navy SEALs Lead and Win

Jocko Willink, Leif Babin, The Dichotomy of Leadership

Barry W. Boehm, Software Engineering Economics

Donella H. Meadows, Thinking in Systems: A Primer

Andrew Hunt, David Thomas, The Pragmatic Programmer: Your Journey to Mastery

Ken Auer, Roy Miller, Extreme Programming Applied: Playing to Win

William C. Wake, Extreme Programming Explored

James Shore et al., The Art of Agile Development (2nd edition)

Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humble, Gene Kim, Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps

Will Larson, Staff Engineer: Leadership beyond the Management Track

Ryan Holiday, Courage Is Calling and Discipline Is Destiny

Erin Meyer, The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business